Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Emergent Draft of 17 June 2021

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2021

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IDM-Auth.html

This is the 3rd article in a series that presents and

articulates a model of entities and identities that supports the design of

effective information systems. Each is designed to be read as a standalone

article, but are likely to be more fully appreciated if read in sequence. The

series overview is at

http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IDM-O.html.

Series

Overview

[ REPLACE: ]

The field of 'identity management' has been fraught for decades, with the battlefield strewn with the corpses of hundreds of failed schemes, and the techniques in use scarred by innumerable deficiencies. The work reported here reflects the author's longstanding belief that the problems derive from a longstanding mis-fit between designers' conceptions of the need, on the one hand, and the complexities of the real world on the other.

The author's previous endeavours during the period 1990-2010 presented an explicit model of real-world entities and identities that had considerable similarities with the implicit models used in industry and government, but also some important differences. A weakness of that model, however, was that it was not sufficiently grounded in existing theory, and hence was too easily dismissed by critics as being ad hoc. This paper re-visits the problem-area, this time building on prior work in philosophy and the information systems (IS) literature. The establishment of intellectual foundations has given rise to some adjustments to the presentation of the model and the terminology used in describing it.

Among the wide variety of possible philosophical assumptions, an approach is selected that reflects the pragmatic world of IS practice. This is directly relevant to that portion of IS research that seeks to deliver information relevant to IS practice. Given the recent, very strong tendency within the IS discipline towards sophistication and intellectualisation, and preference for addressing other researchers to the effective exclusion of IS professionals, the pragmatic metatheoretic model presented here will not be relevant to all research.

The purpose of the model is to reflect the relevant complexities, and hence to guide organisations in devising architectures and business processes for IS that reflect real-world things and events, with a particular focus on systems in which some of the real-world things are human beings. This extends to such applications as user registration, sign-on and identity management. Inanimate entities are addressed first, enabling a relatively mechanistic approach to be adopted. Expanding the scope of entities to human beings involves much more careful attention to interests, rights and values, necessitating some further layers of complexity in the model.

Organisations have encountered longstanding and ongoing difficulties in the area of identification and authentication, particularly where the entities in question are human beings. I contend that suitable designs depend on a much better appreciation by organisations, and by designers of information systems (IS), of the nature of the phenomena that they seek to document and to exercise control over. That in turn depends on a model that is pragmatic, by which is meant that it is a fit to the needs of IS practitioners, but also reflects insights from relevant aspects of philosophy. This paper, the third in a series, builds on the Pragmatic Model of (Id)Entification in Clarke (2021b) by extending it to the activity of Authorisation, including Access Control.

The paper commences with a recapitulation of the core concepts of the two-level model, including the concepts of Entity and Identity and the associated notions of (Id)Entifier and (Id)Entification as applied to inanimate Objects and Artefacts, and the further articulation required when dealing with humans, organisations and Active-Artefacts.

The notion of authentication is introduced informally. The question is then examined in greater detail of how the justification of assertions relating to the various elements of the initial model can be assessed. The initial focus is on assertions in relation to value, attributes and authority. In each case, authentication of the assertions may or may not require the (Id)Entitification of the parties involved. The additional challenges inherent in the authentication of Entities and Identities are then examined.

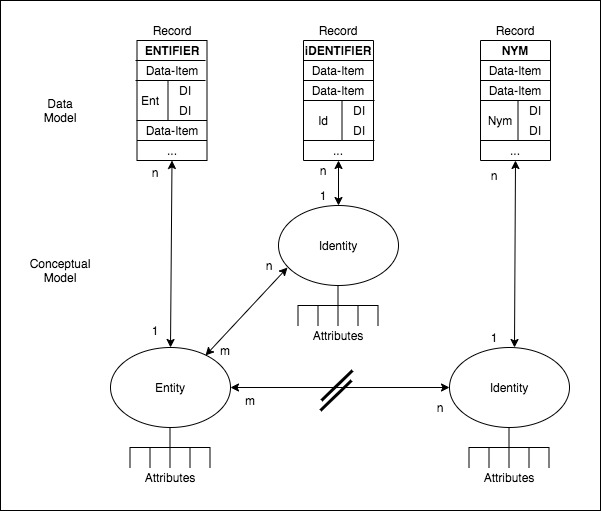

In Clarke (2021b), a two-level model was presented, supported by the diagrammatic presentation in Figure 1. An Entity corresponds with a Real-World Object, and an Identity corresponds with a presentation or role played by one or more Entities. Records are associated with either Entities or Identities by means of particular Data-Items, referred to as Entifiers and Identifiers respectively. Where the Relationship between an Identity and an underlying Entity cannot be established, the term Identifier is inappropriate, and the term Nym applied instead. The basic features of the model can deal with inanimate Objects and Artefacts. Further articulation was shown to be needed when dealing with Virtual Entities, with humans and organisations, and with Active-Artefacts.

The presentation of the two-level model had its focus on distinguishing the concepts needed to capture sufficient of the richness of the Real World. In doing so, it left aside questions of how reliable the assertions are that are inherent in Data-Item-Values stored in Records that purport to relate to particular properties of particular Real-World things. The following section discusses the notion of assertions and their authentication, and lays the groundwork for the subsequent discussion of the process of authenticating several different categories of assertion.

In order to extend the pragmatic model of (Id)Entification to authentication, it is necessary to first consider the broad notion of authentication, and disentangle some misunderstandings of the real world that have pervaded information systems in business and government for many decades, resulting in poor performance of many systems. The following section will consider the particular categories of Assertion.

Because the presentation of ideas in this section is necessarily lengthy and a little laborious, a preview is provided using the archetypal cartoon in Figure 1, which captured the mood at the dawn of the cyberspace era.

Steiner P., The New Yorker, 5 July 1993

Several elements relevant to this paper can be discerned in the cartoon:

If there is a moral to be found in the cartoon (which the cartoonist denies was his purpose), it might be that, when you're using the Internet, you have only a limited amount of information available to you, and you need to be cautious about assumptions you make. In particular situations, there are various things that you might find worth authenticating before you place reliance on information, or take actions. Examples of such situations include where you provide your credit card details, utter confidences to your conversation-partner, open a file that someone has sent you, or pass on information you've received, such as investment tips and rumours about celebrities.

In such circumstances, you might be well-advised to collect some information about one or more of the following:

These various kinds of checking may be entirely independent from one another. In particular, knowing who your conversation-partner is, is not a pre-condition for knowing the others. For example, if your bank confirms that the requisite funds have arrived in your account, you can carry out your part of the bargain with confidence, without knowing which person (or dog) you sold your goods or services to. Similarly, an on-line grief counsellor doesn't need to know the driver's licence number or commonly-used name of a client, provided that they're confident that it's the same 'Bill' or 'Susan' that they were talking to yesterday. And 'Bill' or 'Susan', while they may seek assurance about the counsellor's qualifications and undertakings of confidentiality, are not likely to seek (and are even less likely to be provided with) the counsellor's commonly-used name, home-address and home telephone number.

The term 'Assertion' is used in the manner of OED 4. "declaration, affirmation, averment", as a declaration of the truth of some statement. Assertions are of many kinds. Assertions as to facts, and associated issues such as misinformation, disinformation and 'fake news', are addressed in the sixth paper in this series. The focus in this paper is on assertions of value, of having a particular Attribute, of having authority to perform a particular act, of being an Entity, or being the or an Entity appropriate to use a particular Identity. There has been a tendency in business and government to focus on 'identity authentication' to the exclusion of other forms of authentication, and to confuse it with 'entity authentication'. This section considers each of the categories of assertion, in order to construct an appropriate framework for evaluating which are the appropriate assertions to focus on in any particular situation, and presents definitions of the key terms that reflect and build upon the main body of the model presented in the previous paper.

The term 'Authentication' refers to the process whereby a suitable degree of confidence is established about the truth of an assertion. It is common in the IT industry for the term 'Verification', or sometimes 'Validation', to be used to refer to the process of establishing the truth of an Assertion. This leads many people to infer that the process delivers truth (or 'verity'). In the large majority of circumstances, the result is not in any sense a truth, but rather a degree of assurance of the assertion's reliability. The less boisterous and self-confident term Authentication is accordingly much more appropriate, in order to avoid misleading implications.

One reason that claims of proven truth are generally over-statements is that the real world is complex and not directly accessible. Human experience of phenomena is filtered by human perceptive and cognitive apparatus. Technological aids are designed with particular purposes in mind, they sense and measure only some aspects of particular phenomena, and they assume away a range of contingencies. Added to that, high-reliability authentication processes are generally costly to all parties concerned, in terms of monetary value, time and convenience, and intrusiveness.

Processes become more complex and less reliable where they need to cope with non-compliance by some parties, and particularly where the processes are subject to countermeasures by some of the parties involved. Organisations generally select a trade-off between the various costs, reliability, and acceptability to the affected individuals. This inevitably results in shortfalls in the quality of the Assertion Authentication process and its conclusions.

A variety of techniques and tools are used in order to a establish suitable degrees of confidence about the truth of the various kinds of assertion. Authentication processes depend on evidence, a term which is used here in a manner closely related to OED III, 6: "Grounds for belief; facts or observations adduced in support of a conclusion or statement; the available body of information indicating whether an opinion or proposition is true or valid". Evidence is a generic term for things that assist in supporting an assertion, or resolving facts at issue. An individual item of Evidence is usefully referred to as an Authenticator. A common form of Authenticator is a Document, by which is meant content of any form and expressed in any medium, often text but possibly tables, diagrams, images, video or sound. Content on paper, or its electronic equivalent, continues to be a primary form.

Some Authenticators carry the imprimatur of some authority, such as a registrar. These are usefully referred to as a Credential. Common examples of Credentials are Documents issued by some kind of authority that has, or is assumed to have, undertaken some form of Authentication prior to issuing it, such as a birth certificate, certificate of naturalisation, marriage certificate, passport, driver's licence (and, in some jurisdictions, non-driver's 'licence'), employer-issued building security card, credit card, club membership card, statutory declaration, affidavit, letter of introduction.

An Authenticator may already exist. Alternatively, an Authenticator may be created by an organisation and agreed with or issued to a person. This is commonly performed during the Enrolment phase, when a new party registers with an organisation. A frequently-used approach is to conduct a first-round of reasonably thorough Authentication activities, create a Record for the (Id)Entity - a sub-process sometimes referred to as Registration - and then establish means whereby an effective but also efficient Authentication process can be conducted on the subsequent occasions when a party presents. An Authenticator issued by a relevant party enables a simple, fast and cheap Authentication process on future occasions. Passwords and PINs are examples of tools used in this manner.

The term 'Token' refers to a recording medium on which useful Data is recorded. As discussed in the previous paper, Tokens are usefully applied to the storage of machine-readable copies of (Id)Entifiers. Examples include 'identity cards' (especially 'photo-id'), turnaround documents, tickets issued to Natural Persons required to wait in a queue, and smartcards and 'dongles' designed to be used in conjunction with standalone and networked computing devices. They may also contain Authenticators generally, and Credentials in particular. Security features may be necessary, in order to provide confidence in the validity of the Token and its contents, such as hidden graphic features to guard against forged Tokens, and cryptographic features to guard against manipulation of the content. Measures may also be needed in an endeavour to tie the Token in some manner with the particular Entity that is intended to be its exclusive user.

Where the subject of the assertion is a passive Object, Artefact or even animal, the Authentication process is limited to checking the elements of the Assertion against Evidence that is already held, or is acquired from, or accessed at, some other source that is considered to be both reliable and independent of any party that stands to gain from masquerade or misinformation.

On the other hand, humans, organisations (through their human agents) and Active Artefacts can participate in the Authentication process, in particular in a 'Challenge-Response' sequence. This involves a request or 'challenge' to the relevant party for an Authenticator, and an answer or action in response. Examples of Authenticators relevant to each of the important categories of Assertion are provided in the following sections.

A range of risk factors impinge on the quality of Authentication processes. Of especial importance is the need to achieve an appropriate balance between the harm arising from:

Sources of poor quality include the following:

Where quality shortfalls occur, additional considerations come into play, including the following:

Quality is a substantially greater challenge where other parties are motivated to achieve false positives or false negatives. Safeguards are needed to limit the extent to which such parties may succeed in having Assertions wrongly authenticated or wrongly rejected, in order to gain advantages for themselves or others. Techniques such as channel encryption (in particular SSL/TLS), and one-time password schemes, are used for these purposes. Each safeguard has vulnerabilities, and is subject to threats.

The level of assurance of an Authentication mechanism depends on the extent of protections against abuse, and hence on whether it can be effectively repudiated by the entity concerned. It is useful to distinguish multiple quality-levels of Authentication, such as unauthenticated, weakly authenticated, moderately authenticated and strongly authenticated. Strong authentication is associated with the concept of 'absolute trust', which has currency in some military and national security applications. Business enterprises and most government agencies generally adopt 'risk management' approaches, which accept lower levels of assurance in return for processes that are less expensive, more practical, easier to implement and use, and less intrusive.

This section considers in turn each of the categories of Assertion that is prominent in IS in business and government, and the approaches adopted to the Authentication of those Assertions.

A great deal of the discussion of Authentication in the IS discipline is in the context of commerce, and particularly commerce conducted at least in part by electronic means. The focus in such contexts is on 'Value' in the sense of perceived "material or monetary worth" (OED I 1a). Hence the foundational form of Value Assertion is that a Tradable Item has economic value, or has Attributes that underpin economic value. Value exists in all forms of Tradable Items, including Objects, Artefacts and Virtual Artefacts. Value also exists in cash, in the sense of 'ready money' widely accepted as a basis for value-exchange, and cash-like assets, which may encompass short-term loans, and extend to vouchers such as certificates and tickets. Value-Authentication then is the process of establishing confidence in a Value-Assertion.

Examples of Authenticators applicable to Assertions relating to Tradable Items include valuation reports on real estate and valuable Objects such as gems and artworks, inspectors' reports on livestock, and pedigree certificates for pets and breeding stock.

In the case of cash-like assets, examples of Value Authentication include:

In a great deal of conventional commerce, Value Authentication without identity is a primary means whereby trust is achieved. In e-commerce, however, an aberration has arisen: in its early years, the sole practical payment mechanism was through the transmission of credit card details, which carry an Identifier of the cardholder. Payment mechanisms that do not have an (Id)Entifier associated with them have been conceived, designed, prototyped, implemented, and trialled, but have not yet been widely adopted.

One reason for slow adoption of nymous value-transfer is the opposition of tax collection agencies, which rely on the ability to associate the arrival of funds that represent taxable income with the (Id)Entity that received them. There is, of course, the scope for techniques that deliver Pseudonymous value-transfer, with the protections against (Id)Entification readily surmountable by the relevant tax agency, but not by other organisations and individuals. Chaumian eCash operated in this manner during the period 1995-98 (Chaum 1985), whereas, since 2014, privacy coins such as Monero, and to a lesser extent Bitcoin and other blockchain-based currencies since 2009, are somewhat resistant to visibility to taxation agencies.

An Attribute-Assertion declares that an (Id)Entity-Instance has a particular Attribute. Attribute-Authentication comprises two elements. The first is an evaluation of the substantive claim. This may use Evidence gathered by the organisation itself, such as comparison of an assertion of a gem's weight in carats against an independent measure, or the claimed term and interest-rate of a mortgage loan may be checked against the relevant Documents. Alternatively, it may involve the inspection of some kind of Credential. A party that accepts a Credential as being in itself sufficient Evidence is a Relying Party. For example, an Assertion that a cargo-container has the Attribute 'clean' may rely on an inspector's certificate.

The second check is whether the association of the Attribute with the (Id)Entity-Instance is justified. This may depend on checking the (Id)Entifier on the claim against that on the Authenticator or Credential.

Considerably greater challenges arise where an Attribute Assertion is about a human. The first test is whether Evidence supports the part of the Assertion that declares the Attribute, e.g. whether a person is within an age-range appropriate to some category of transaction (frequently, younger-than or older-than some age), or is a member of a particular association, is a tradesperson eligible to buy at wholesale prices, or has a particular educational or other qualification. An example of an Authenticator elating to a person's residential address is a copy of a recent utilities invoice. Examples of Credentials include a testamur issued by an educational institution as evidence of qualifications, a certificate issued by a registration authority evidencing the right to practise in a controlled profession, or the right to drive a particular kind of motor vehicle, or vaccination against a particular disease.

Many approaches are heavily dependent upon the existence and reliability of an issuer of relevant Credentials. In most jurisdictions, a proxy-provider of date-of-birth and age Credentials is relied upon, in the form of the government agency that administers driver-licensing (or such outsourced service providers as that agency in turn relies on). The Credential-issuer needs to perform a one-time action to determine a human Entity-Instance's date of birth. In practice, there are circumstances in which this is challenging. Thereafter, all Relying Parties treat an assertion of age as true if the Credential supports it, with some, often slim, authentication performed of the relationship between the Credential and the human Entity-Instance presenting it.

Another important example of an Attribute-Assertion is of the form 'the (Id)Entity that originated this message did so from, or in respect of, a particular location, within some tolerance range'. This might involve location and tracking technologies such as the triangulation of cell-phone signals, or self-reported location, purportedly on the basis of Data sourced from a global positioning system (GPS). Location authentication has application in a variety of contexts, including:

As is the case with all Attributes, mechanisms are needed that support location authentication with and without (Id)Entity.

A particular form of Attribute is sufficiently important to warrant special attention. An Authority-Assertion is one which declares a principal-agent relationship, whereby one (Id)Entity has the legal capacity to perform particular act(s) on behalf of another (Id)Entity, such as binding them in contract. The representative is referred to as an agent, and the party being represented is called the principal.

Agents may be appointed to act on behalf of people, or of organisations. It is common to evidence the Relationship by means of a document generically referred to as a power of attorney. In many cases, there is a chain of agency Relationships, passing through multiple organisations and individuals. An example is an employee of a customs agency, which is acting on behalf of another customs agency that operates in a location overseas, which in turn acts for an exporter. A chain of principal-agent relationships among bodies corporate culminates in a principal-agent relationship between the last company and its employee. In principle, the Authority-Authentication of an agent requires inspection and testing of the evidence for the complete series of delegations. In practice, such inspections and testing may not be performed, and in many cases they may be impractical anyway. Society the economy run on a remarkable amount of trust, which gives rise to vulnerabilities that some actors exploit.

Until recently, agents had always been human. However, increasing numbers of examples have emerged of acts delegated to Active Artefacts, through such means as automated telephone, fax and email response; automated re-ordering; program trading; and other forms of software agent. Legislatures and courts have become increasingly willing to accept acts of Active Artefacts as being binding on the principal, at least under some circumstances.

In many cases, messages communicate the (Id)Entities of the agent and the principal. Circumstances arise, on the other hand, in which either or both of the agent and the principal may use a Nym. In addition, the fact that it is a Nym may or may not be disclosed. For example, it is reasonably common for principals to use Anonymity or Pseudonymity when selling works of art and moderately-sized shareholdings. Hence Authentication of principal-agent relationships needs to make allowance for agency with and without (Id)Entity.

The (Id)Entification and Authentication schemes operated by business enterprises must be sufficiently sophisticated to distinguish between the acts and (Id)Entities of principals, of intermediate agents, and of ultimate agents. Care is needed to ensure not only that the Relationship between principal and agent exists at the relevant time, but also that it actually encompasses the kind of transaction being conducted, and does not exceed any limitations on the agent's power to act on behalf of, and bind, the principal. A further complication is that an agent may act for multiple principals, and a principal may be represented by multiple agents. This results in multiple Credentials, and the scope for conflicts of interest that need to be managed.

Analogous arrangements have been envisaged for the electronic context, applying cryptographic techniques. One approach would be to authenticate the (Id)Entity of the individual and/or organisation, and then check for an appropriate match on a register of (Id)Entities authorised to act on behalf of the principal. Such a register might be implemented in distributed fashion, by setting an indicator within the person's own digital-signature chip-card.

Another approach is direct Authentication of an authorisation. For example, an organisation's private signing-key could be used on the relevant instrument, with authentication comprising confirmation using the organisation's widely available public key. This approach avoids unnecessary declaration and Authentication of the (Id)Entity of the agent. In such a scheme, management of the risk of appropriation or theft of the private signing-key is of course essential.

Many circumstances exist in which the Credential identifies the person. This is not actually necessary, however. All that is needed is some means whereby the Credential is reliably associated with the (Id)Entity presenting the Credential. For example, a series of challenges for information can be sufficient to establish that a person qualifies for entry to secure premises, without even knowing their (Id)Entity, let alone authenticating it.

Moreover, even where the process of Attribute Authentication involves the provision of an (Id)Entifier, there may be no need to record anything more than the fact that Authentication was performed. In this way, the Transaction is not identified. One example of this is the inspection of so-called 'photo-id', without recording the (Id)Entifier displayed on the card. In addition, IS can be designed to authenticate each party's eligibility to conduct a Transaction (e.g. is a member of an appropriate category, or has a particular Attribute) without disclosing the party's actual (Id)Entity. A too expressly designed for this purpose is U-Prove digital certificates, which authenticate an (Id)Entity's Attributes without disclosing any (Id)Entifiers (Brands 2000).

Authority-Authentication can also be performed without disclosure of the (Id)Entity of either the agent or the principal. This mirrors the various arrangements in auctions and exchanges for the protection of the (Id)Entity/ies of one or more of the parties involved in transactions.

[ NOT YET REVIEWED: ]

An Entity Assertion involves an Entifier being argued to appropriately associate Data with a particular Entity-Instance, and hence, via the or an Entifier, with one or more particular Records. The term Entity Authentication refers to the process whereby a party establishes a degree of confidence in an Entity Assertion. The process comprises cross-checking against additional evidence the Entity-Instance signified by the Entifier acquired during the Entification process.

In the case of objects, a distinction needs to be made between Natural Objects, human-made objects, commonly referred to as Artefacts and human-devised Virtual Artefacts that lack corporeal form (such as electronic publications, trademarks which date to the 13th century, and loans which date to 1000BC). Sub-categories of Artefacts and Virtual Artefacts need to be recognised: those capable of decision and action, referred to in this paper as Active Artefacts (such as drones) and Active Virtual Artefacts (such as processes running in computer-devices).

The Entification of an Entity-Instance depends on the gathering of an Entifier of the Natural Object or Artefact. It is uncommon for Natural Objects to evidence a natural biometric, that is to say a physical property that is sufficiently easy to measure, and sufficient to distinguish one object from all other similar objects. In the case of most Natural Objects, this matters little, because pebbles, rocks, stones and individual specimens of plants, even large trees, are only accorded individual attention in IS where the value is very high, e.g. gold. Most ores are treated as undifferentiated commodities - although commercial factors may dictate that some sub-categories be distinguished, as occurs with coal (e.g. lignite from anthracite). Difficulties arise, however, with raw gems and meteorites, and rare or otherwise valuable biological specimens, e.g. of large trees and of plant species facing extinction.

Fluids, including liquids such as crude oil, petroleum products, water and mercury, and gasses such as oxygen and helium occur naturally as a volume rather than differentiable elements. In this case, stocks and flows are carefully accounted for, as a quantum rather than as individual items. Even in these cases, however, sub-categories may be distinguished, as occurs in thec ase of crude oil (e.g. Brent Blend from West Texas Intermediate - WTI).

Artefacts are in many cases devised to as to be distinguishable, by assigning a code that is inherently unique, at least within the relevant context. (For example, it matters little if two distant countries assign the same vehicle registration number to different cars, whereas it does matter if tow jurisdictions with common borders do so). Authentication of a cargo-container requires confirmatory evidence of its BIC or of one or more Entity-Attributes such as container-type code, length and height.

On the other hand, artefacts that are inexpensive, small, large-volume, short-lived and/or seem unlikely to need careful tracking, generally do not warrant the expense and effort involved in the creation and management of Entifiers. Examples include paper-clips, clothes-pegs, house-bricks and even needles for use in syringes. In commercial terms, these are commodities rather than individually-identifable products.

Because Virtual Artefacts such as loans, shares and digital money lack corporeal form, the practical application of Entification to creates challenges. Those with low or no value may be simply ignored by IS. Some Virtual Artefacts with significant commercial or other value are assigned codes as Entifiers, such as loans secured by mortgages over specified property. Entity-Assertion Authentication requires Evidence in support of the proposition that the appropriate association is being made between Entifier and Entity-Instance.

Other valuable Virtual Artefacts, however, are treated as commodities, including shares and digital money such as funds deposited with corporations for loan-periods or at call. These are managed in much the same manner as fluids, as quanta of stocks and flows. The running balance of the quantum is maintained in a derivative Virtual Artefact commonly referred to as an Account, which is assigned a code as its Entifier.

In the case of Entity Authentication for Active Artefacts such as a computer or mobile phone, a test needs to be conducted of the claim that the device is properly distinguished by means of a relevant Entifier (such as the processor-id or mobile-phone-id). For example, if an Entifier is asserted at the same time in two local networks or cells, or in a new cell very shortly after being in a cell a considerable distance from the previous cell, it would appear that at least one of the devices is conducting masquerade. Similarly, Entity Authentication for Active Virtual Objects, in particular a process running in a computing device, requires a check of the Entifier, perhaps via a proxy such as the IP-Address and Port-Number.

Some categories of animals are treated as objects, and assigned Entifiers. For cattle and some other livestock, this is by means of the assignment of a code, and the embedment of a machine-readable version of it in an attached Token, in that context commonly referred to as a tag. For pets, the norm has been to inject the Token, in the form of a chip bearing the machine-readable code. Tracking of endangered wildlife is commonly by means of tags and collars. In some cases, however, implanted chips are used, such as in rhinoceros horns. In all of these cases, Entity-Assertion Authentication seeks assurance that the association between Entifier and Entity-Instance is appropriate.

In the case of humans, the Entification of an Entity-Instance has, to date, only in relatively rare cases involved an imposed Entifier such as a tightly-linked or embedded code. Exceptions include anklets imposed on people in open prisons, and temporary tags on patients (or on the hospital beds they are lying in). In most cases, Entification depends on the gathering of an Entifier of the person, i.e. a biometric. This appears to have not yet become economically viable for even the most valuable livestock, but has been economically justified by some organisations for application to the management of humans, despite the imposition of institutional or market power over individuals that it entails. The Entity-Assertion Authentication process involves a cross-check of the Entifier against a reference measure. The term 'Evidence of Entity (EOE)' refers to Evidence that assists in Authentication of an Assertion relating to Entity, which is a reference measure of the appropriate biometric, or some proxy for it. The term is not in common usage, because most discussions conflate Entity with Identity. As the model and analysis presented in this series of papers makes clear, it needs to become a mainstream term.

The conduct of Entity Authentication for a human, dependent as it is on a biometric, may assess one or several of 'what the person does' (such as the act of providing a written signature, or the micro-actions involved in the keying of a password), 'what the person is' (a biometric), or 'what the person is now' (i.e. an imposed biometric), by comparing the measure against some previously collected and stored measure of the same thing.

All such mechanisms involve significant challenges in terms of quality and security. Measures necessary to assure adequate quality of the human Entity Authentication process include:

Such processes are expensive, inconvenient, intrusive, and threatening. Unlike the Entification process, however, they involve a 1-to-1 comparison between a new measure and a single previously-recorded measure. Biometric authentication is therefore capable of being designed so as to achieve balance among multiple interests, at least in principle (although seldom to date in practice).

Another approach is to provide the person with a Token, which is some physical, or perhaps electronic, object that the person is expected to present as evidence that they are the person concerned. Such a Token may carry the reference-measure of one or more biometrics (or, much less dangerously, a hash of a biometric).

Authenticators arising from a Challenge-Response sequence relevant to the Authentication of Assertions of Entity are what the person or artefact 'knows':

The Entification of organisations is a very different matter from that of Real-World objects, artefacts and humans, and much more akin to the situation that applies to Virtual Artefacts. Organisations are assigned Entifiers in the form of registered names, and in many jurisdictions also codes, for business enterprises generally, or for corporations specifically. The Entification process for an Entity-Instance involves the gathering of an Entifier of the organisation. The process of Entity-Authentication needs to deliver adequate evidence that the Entity-Instance is in fact the one to which the Entifier that has been gathered is properly associated. However, because of the lack of a corporeal existence, the Entity-Authentication process is challenging. Organisations' incorporeality means that they are unable to perform actions that affect the real world, they can only, for example, enter into contracts, place orders, receive deliveries, instigate payments, accept orders, and initiate deliveries. This is achieved by humans performing those acts on their behalf.

Authentication can only be performed by checking the assertions of humans who are capable of acting in the real world. A check also needs to be performed that the person has the right and power to act on behalf of the Entity-Instance associated with the Entifier. The nominally highest-quality authentication of a corporation's (id)entity and actions was once the affixing of the company's seal to a document, over-signed by authorised officers. This was actually of low quality, because both the seal and the signatures were easy to spoof, and very difficult to check. With the emergence of e-commerce during the last quarter-century, requirements for use of a company seal have been progressively rescinded.

One common proxy approach is to check that communications appear to come from the relevant organisation. Reliance on authentic(-looking) letterhead and the From: line in an email is inadvisable. The reliability of web-site certification is also very low, because digital certificates, while they attest to strong protections for transmissions against thirds parties, they offer no memaningful warranty that the second party is who they claim to be.

It has often been claimed that electronic signatures in general, and digital signatures in particular, offer the prospect of higher levels of confidence. But in addition to the security measures needed in respect of the person's digital signature keys, further measures are needed, in order to reduce the likelihood of error or fraud through the misapplication of the organisation's powers. A softer but often more effective technique is confirmatory communications via a second channel established independently from the first, e.g. call-back to a telephone number, or email-exchange via an address, acquired from some other source.

[ NOT YET ORGANISED: ]

An Identity Assertion involves an Identifier being argued to appropriately associate Data with a particular Identity-Instance, and hence, via the or an Identifier, with one or more particular Records. The term Identity Authentication refers to the process whereby a party establishes a degree of confidence in an Identity Assertion. The process comprises cross-checking against additional evidence the Identity-Instance signified by the Identifier acquired during the Identification process.

A party is satisfying itself that that another party is:

Authentication is expensive, and hence the degree of effort invested needs to reflect the likelihood or accidental and intentional error, and of the harm that would arise if error occurred. One approach is to gather additional Identifiers, i.e. two or more of the mainstream categories of Identifier, comprising names and codes. Another is to collect and evaluate Authenticators.

Evidence of Identity (EOI) is Evidence that assists in Authentication of an Assertion relating to Identity. It is in common usage, but is all-too-often usurped by the inappropriate term Proof of Identity (POI). The term 'proof' implies Evidence that establishes an incontrovertibly true assertion. This is an unachievable standard in a simplified model of a complex and contestable Real World.

All other things being equal, two-factor authentication is regarded as being stronger than single-factor authentication, and three-factor as stronger again, in both cases provided that the factors are independent from one another. In the case of human identities, several forms of EOI are used. They include 'what the person knows' (such as a password or PIN) and 'what the person has' (such as documents and tokens).

Natural Objects,

Artefacts

Virtual Artefacts

Active Artefacts and Active Virtual Artefacts

Animals

Humans

It is common for security analysts to discuss 'what the person does' and 'what the person is' as though they were forms of identity authenticator. The pragmatic model presented in this paper makes clear that this is seriously mistaken, because those activities are forms of Entity Authentication. Many human Entity-Instances use multiple Identity-Instances, and many Identity-Instances are used by multiple human Entity-Instances. Confirmation that a Identity-Instance is being appropriately used most commonly depends on combinations of 'what the person' has and 'what the person knows'.

The oft-made error of confusing Entity Authentication with Identity Authentication is significant and harmful. Firstly, where human Entity-Authentication is checked by means of a biometric, it is still logically necessary to establish that the Entity-Instance in question has and is appropriately using the Identity-Instance in question. ('Is that person the current Club Treasurer'?).

However, it was also noted above that authentication of human Identities is challenging, expensive, onerous and even demeaning. Authentication of human Entities is substantially more so. It is undermined by a whole litany of difficulties in achieving adequate measurement and comparison quality. It suffers serious security vulnerabilities. And it is highly personally intrusive and degrading (Clarke 2002a).

Gathering more than one Identifier may be of value, provided that the two Identifiers have some degree of independent existence. A more effective approach is to collect and evaluate Authenticators. For example, the person may be asked to demonstrate that they have some knowledge that only that person could be expected to be able to provide. In counter and telephone services for consumers and citizens, for example, the person may be asked for their birthdate, or their mother's or wife's maiden name. Further authenticators may be issued and managed by organisations, such as a password, or a 'personal identification number' (PIN).

Another approach is to provide the person with a Token, which is some physical, or perhaps electronic, object that the person is expected to present as evidence that they are the person concerned. Such a Token may carry a copy of a secret (or, better, a hash of the secret), or a set of one-time passwords, or a digital signing key and the ability to generate a digital signature.

Token-based schemes are very effective in tightly controlled environments, as a variant on the 'turnaround document' approach: the person first presents at a counter, then must wait in a large, anonymous area prior to visiting the counter a second time. If an Authenticator such as a numbered service-ticket is issued on the first occasion, and interchange or theft of the Authenticator is unlikely, then it is an Identity Authenticator within that limited context.

Another common form of Token is a card issued by an organisation. Such cards are generally provided on the basis of documentary evidence of Identity presented by the person. Examples of such documents include birth certificates, marriage certificates, passports, drivers' licences (and, in some jurisdictions, non-drivers' 'licences'), employer-issued building security cards, credit cards, club membership cards, statutory declarations, affidavits, letters of introduction, and invoices from utilities. In the electronic arena, a form of Token that might be used for identity authentication is a digital signature consistent with the public key attested to by a digital certificate.

Difficulties arise with all forms of Authenticators of Identity. Apart from the costs and inconveniences involved, documentary evidence is fundamentally unreliable. Ultimately, all documents depend on some seed document, most commonly a birth certificate; and such documents do not embody any reliable association with an Identity.

Reflecting the high degree of unreliability of each of the approaches to human Identity Authentication, organisations that have a need for relatively high levels of confidence commonly require one or more Tokens, supplemented by knowledge-based tests. This is frequently highly inconvenient for people, often demeaning, and in many cases impractical. Corporations and government agencies often use their power over individuals to achieve compliance, rather than seeking consensus among stakeholders about the appropriate balance between social control and personal freedoms.

The laws in some countries require the presentation of a set of credentials (the so-called '100-point' scheme), with high weightings assigned to a passport, a driver's licence, supplemented by lower weightings for evidence of occupancy at an address such as a rates notice and utilities invoices

token:

a token (a card) may be presented, bearing an identifier (a code), together with a representation of the person's appearance (a photograph) and/or a sample signature (for visual authentication processes) or an encoded PIN (for automated authentication processes)

Evidence of Ownership (EOO) is Evidence that assists in Authentication of an Assertion that a particular (Id)Entity is the appropriate possessor of a Credential. Sometimes referred to by the less appropriate term Proof of Ownership (POO). A suggestion that Evidence is determinative of truth in relation to an Assertion relating to Identity is inconsistent with models of a complex Real World.

all schemes depend on tokens that are subject to the 'entry-point paradox' (Clarke 1994b).

Authenticators arising from a Challenge-Response sequence relevant to the Authentication of Assertions of Identity are what the person or artefact 'knows':

Organisations

TEXT

via relevant a human (Id)Entity-Instance as a proxy, but also checking the linkage between the (Id)Entity-Instance and the power claimed

[ From http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-1002.html#MAc

Ì Cross-checked against http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-Gloss-1002.html

Ì Checked against http://rogerclarke.com/EC/AuthModel.html

Ì Cross-checked against http://rogerclarke.com/DV/IdAuthFundas.html

Ì Cross-checked against http://rogerclarke.com/EC/IdAuthGloss.html

TEXT

Brands S.A. (2000) 'Rethinking Public Key Infrastructures and Digital Certificates: Building in Privacy' MIT Press, 2000

Chaum D. (1985) 'Security Without Identification: Transaction Systems To Make Big Brother Obsolete' Communications of the ACM 28, 10 (October 1985) 1030-1044, at http://crypto.cs.mcgill.ca/~crepeau/chaum-CACM.pdf

Miscione G., Ziolkowski R., Zavolokina L. & Schwabe G. (2018) 'Tribal Governance: The Business of Blockchain Authentication' Proc. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-51), 3-6 January 2018, at https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/bitstream/10197/9376/1/Authentication_HICSS.pdf

[TO BE CULLED:]

Adams B. (1997) '' Deseret News, 20 November 1997, at http://www.deseretnews.com/article/595933/Novell-introduces-goal-putting-a-friendly-face-on-computer-networking.html?pg=all

Chen P.P.S. (1976) 'The Entity-Relationship Model - Toward a Unified View of Data' ACM Transactions on Database Systems 1 (March 1976) 9-36

Clarke R. (1993) 'Computer Matching and Digital Identity' Proc. Computers Freedom & Privacy, Burlingame CA, March 1993, at http://cpsr.org/prevsite/conferences/cfp93/clarke.html/, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/CFP93.html

Clarke R. (1994a) 'The Digital Persona and its Application to Data Surveillance', The Information Society 10, 2 (June 1994)', at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/DigPersona.html

Clarke R. (1994b) 'Human Identification in Information Systems: Management Challenges and Public Policy Issues' Information Technology & People 7,4 (December 1994) 6-37, at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/HumanID.html

Clarke R. (2001a) 'Authentication: A Sufficiently Rich Model to Enable e-Business' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, December 2001, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/AuthModel.html

Clarke R. (2001b) 'The Re-Invention of Public Key Infrastructure' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 22 December 2001, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/PKIReinv.html

Clarke R. (2003) 'Authentication Re-visited: How Public Key Infrastructure Could Yet Prosper' Proc. 16th Int'l eCommerce Conf., Bled, Slovenia, 9-11 June 2003, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled03.html

Clarke R. (2010a) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation' Proc. IDIS 2009 - The 2nd Multidisciplinary Workshop on Identity in the Information Society, LSE, London, June 2009, rev. February 2010 at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010b) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Supplementary Materials' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-Supp-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010c) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Glossary of Terms' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-Gloss-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010d) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Application of the Model' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-App-1002.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'Promise Unfulfilled: The Digital Persona Concept, Two Decades Later' Information Technology & People 27, 2 (Jun 2014) 182 - 207, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/ID/DP12.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'What Drones Inherit from Their Ancestors' Computer Law & Security Review 30, 3 (June 2014) 247-262, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/Drones-I.html

Clarke R. (2019) 'Risks Inherent in the Digital Surveillance Economy: A Research Agenda' Journal of Information Technology 34, 1 (March 2019) 59-80, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/DSE.html

Clarke R. (2021) ' A Pragmatic Metatheoretic Model for Information Systems Practice and Research' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, May 2021, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/POEisy.html

Newell S. & Marabelli M. (2015) 'Strategic Opportunities (and Challenges) of Algorithmic Decision-Making: A Call for Action on the Long-Term Societal Effects of 'Datification'' The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 24, 1 (2015) 3-14, at http://marcomarabelli.com/Newell-Marabelli-JSIS-2015.pdf

Zuboff S. (2015) 'Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization' Journal of Information Technology 30, 1 (March 2015) 75-89, at https://cryptome.org/2015/07/big-other.pdf

[ TO BE CULLED and/or MOVED TO THE SERIES OEVRVIEW? ]

This Working Paper draws on, consolidates and extends a long series of more than 10 working papers and 5 refereed publications. They are listed here as a matter of record and as a form of declaration of re-use or 'self-plagiarism'. Some are cited in the Working Paper. The conceptualisations and model have developed a great deal during the course of the more than 30 years over which the papers extend. There are accordingly inconsistencies both among them, and between the earlier papers and the present work. This includes considerable adjustment from the most iteration of the model from the version published in 2010, in order to achieve greater consistency with prior literature and the subsequently proposed pragmatic metatheoretical model.

Clarke R. (1990) 'Information Systems: The Scope of the Domain' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, January 1990, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/ISDefn.html

Clarke R. (1992) 'Fundamentals of Information Systems' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, September 1992, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/ISFundas.html

Clarke R. (1992) 'Knowledge' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, September 1992, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/Know.html

Clarke R. (1994a) 'The Digital Persona and its Application to Data Surveillance', The Information Society 10, 2 (June 1994)', at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/DigPersona.html

Clarke R. (1994) 'Human Identification in Information Systems: Management Challenges and Public Policy Issues' Information Technology & People 7,4 (December 1994) 6-37, at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/HumanID.html

Dempsey G. (1999) 'Revisiting Intellectual Property Policy: Information Economics for the Information Age' Prometheus 17, 1 (March 1999) 33-40, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/DempseyProm.html

Clarke R. (2001) 'Information Management, Information Policy, Knowledge Management and Knowledge Organisations' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, March 2001, at http://xamax.com.au/EC/IMKM.html

Clarke R. (2003) 'Key Insights from the Philosophy of Science' Xamax Consultancy Prt Ltd, January 2003, slide-set, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/10-PhilSci-5.pdf

Clarke R. (2003) 'Authentication Re-visited: How Public Key Infrastructure Could Yet Prosper' Proc. 16th Int'l eCommerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, June 2003, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled03.html

Clarke R. & Dempsey G. (2004) 'The Economics of Innovation in the Information Industries' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, April 2004, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/EcInnInfInd.html

Clarke R. (2004) 'Identification and Authentication Fundamentals' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, May 2004, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/IdAuthFundas.html

Clarke R. (2004) 'Identification and Authentication: Glossary' Extract from a monograph on 'Identity Management: The Technologies, Their Business Value, Their Problems, and Their Prospects', at http://www.xamax.com.au/EC/IdMngt.html, May 2004, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/IdAuthGloss.html

Clarke R. (2008) 'Terminology Relevant to Identity in the Information Society' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, August 2008, at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/IdTerm.html

Clarke R. (2019) 'Beyond De-Identification: Record Falsification to Disarm Expropriated Data-Sets' Proc. 32nd Bled eConference, June 2019, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/RFED.html

TEXT

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor associated with the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation in UNSW Law, and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 3 April 2021 - Last Amended: 17 June 2021 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/ID/IDM-Auth.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy