Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Emergent Draft of 19 February 2024

For presentation at a research seminar in ANU Law on 27 February 2024

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2024

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/IAA24.html

The slide-set is at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/IAA24.pdf

The term 'impact assessment' has been applied to a wide variety of activities. Some forms, such as technology (impact) assessment (TA), are broad-scale studies conducted primarily by government policy agencies. Others, such as an EU 'fundamantal rights impact assessment' (FRIA) are obligations imposed on organisations that are intending to undertake an intervention into a social or socio-technical system.

Impact Assessments that are regulatory impositions naturally invite the affected organisation to adopt a compliance approach. The activity is perceived as being 'a cost of doing business' rather than 'a part of doing business', and the organisation's motivation is to minimise the financial and organisational costs involved.

This presentation examines the feasibility of integrating impact assessment with organisational processes, such that the organisation perceives the activity to not just incur costs, but also to deliver benefits, and to enable risks to be better understood and better managed.

Entrepreneurs are perceived by politicians to be exciting, and to bring great promise of more economic activity. Entrepreneurial speech, meanwhile, is irresponsibly optimistic and vague; but decision-makers are uncritical and are swept along. Entrepreneurial behaviour is cavalier with other people's money; but investors are lured by the prospect of riches.

Entrepreneurial behaviour can also be cavalier with respect to the quality, impacts and implications of what they produce. Individuals affected by low quality and negative impacts, unlike investors, seldom have the opportunity to avoid the harm inflicted. This may be the case with many kinds of interventions, including new or amended legislation, regulatory measures of other kinds, and adaptation of institutional or sectoral infrastructure due to shifts in market power. It is particularly common with interventions that involve changes in business processes, new applications of technology, and particularly new applications of untested transformative or disruptive technologies.

Despite the risks and the unfair allocation of risks, there is an absence of effective regulation. Governments tolerate bad behaviour in order to avoid 'killing the golden goose' that is assumed to be inherent in each new technology spruiked by technologists and investors.

The term 'impact assessment' is applied to processes that set out to identify future consequences of a current or proposed action. Less briefly, "Impact assessment ... is the process of identifying the future consequences of a current or proposed action ... The concept ... evolved from an initial focus on the biophysical components to a wider definition, including the physical-chemical, biological, visual, cultural and socio-economic components of the ... environment" (IAIA 2009, p.1).

According to the International Association of Impact Assessment (IAIA), the notion includes "a legal and institutional procedure linked to the decision-making process of a planned intervention", and "The issuing of a report ... is not typically an effective way of practicing IA. In some countries, ... the analysis of alternatives is considered the 'heart' ... of the process. Also important to the success of IA is the process of follow-up which assures that recommendations of the IA are implemented and effective" (p.1).

Despite the pervasiveness of projects and programmes of very large scale and impact, and the frequency with which material collateral damage occurs, parliaments, governments and regulatory and oversight agencies have failed to impose on the proponents of schemes the discipline inherent in the conduct of an impact assessment. The purpose of this presentation is to scan the field of impact assessment, and suggest an evolutionary approach whereby some progress may be made towards embedding impact assessment notions into conventional business processes.

The presentation commences by clarifying underlying concepts, culminating in an appreciation of stakeholder perspectives. It then reviews the key aspects of the widely-understood business process of risk assessment (RA). This sets the scene for an outline of how existing processes might be adapted in order to integrate insights into the interests of stakeholders with those of an intervention's sponsor, and thereby discourage designs that have serious deleterious consequences for at least some of those affected by interventions.

The nature of the interests that any particular player has in a situation varies considerably. In business contexts, most stakeholder interests are ultimately financial in nature. This lies on the economic dimension, but is a small-scale view from the perspective of a single player. Broader economic views are taken by vehicles other than joint stock corporations, such as public sector enterprises, joint ventures, public-private partnerships, industry sectors, industry value-chains and industry value-networks. Meanwhile, governments of sub-national jurisdictions, nation-states and supra-national regions (such as the EU and ASEAN) take a much 'bigger picture' economic view.

Many interests of employees are micro-economic, but, for each individual, values on the social dimension also loom large, as reflected in expressions such as work-life balance. Working up the scale of social organisation, increasingly broad notions of social interest emerge at network and community levels, and within geographical regions and societies, but also across other groupings as occurs with dispersed clubs and ethno-lingual diaspora.

The third dimension of the physical enviroment has loomed ever-larger since the middle of the 20th century, as industrial pollution and then anthropomorphic aspects of climate change came into view. In this dimension as well, the conceptions of values and interests are expressed differently at different levels of aggregation, such as local ecologies; biomes, life-types and ecosystem types; and the biosphere. The emergence of 'triple-bottom-line' reporting ostensibly reflects appreciation of all of the economic, social and environmental dimensions (Elkington 1994, Milne and Gray, 2013) and has become entwined with the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Hedman and Heningsson, 2016).

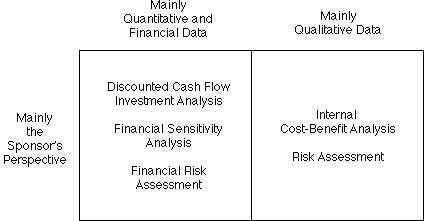

The sponsor of an innovation may be any of the economic vehicles referred to above (joint stock corporation, public sector enterprise, joint venture, public-private partnership). Such organisations typically evaluate possible interventions into socio-technical systems by means of the techniques depicted in Table 1. The most common of the techniques is Business Case Development (BCD) (Schmidt 2005), often supplemented by more exacting techniques such as Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (DCF) (SoW 2013), Net Present Value Analysis (NPV) (Dikov 2020), financial sensitivity analysis (SoW 2013) and financial risk assessment.

(Extracted from Exhibit 1 in Clarke 2008)

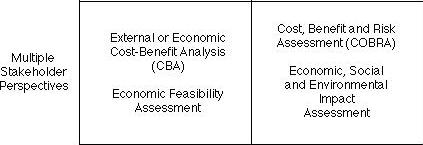

Where a government of, or an individual agency within, a jurisdiction (which may be sub-national, a nation-state or a supra-national region) evaluates an initiative, it may apply business case techniques, but it is much more likely to include public policy considerations, or even use an evaluation technique that is imbued with public values rather than having a predominant focus on narrow-scope economic considerations. See Table 2. The most well-established form is Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) (Stobierski 2019).

(Extracted from Exhibit 1 in Clarke 2008)

The extent to which the dimensions of economic, of social and of environmental values are reflected in the evaluation technique adopted by an intervention's sponsor may therefore fall anywhere across a very broad spectrum.

Impact Assessment, as outlined earlier, is framed far more broadly than business case approaches, in order to address "the future consequences of a current or proposed action". Multiple categories have emerged. Historically, the first two categories to gain traction, EIA/SEA and TA) came from substantially different directions.

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) emerged in the 1960s and was first formalised as early as 1970. It is usefully described as "assessing proposed actions (from policies to projects) for their likely implications for all aspects of the environment, from social through to biophysical, before decisions are made to commit to those actions, and developing appropriate responses to the issues identified in that assessment" (Morgan 2012, p.5). However, "[EIA] practice around the world is dominated by its use at the project level, with particular emphasis on major projects" (p.6). Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is "a way to extend impact assessment to higher level decision-making at policy, programme and plan levels" (p.6).

There appears to remain a considerable amount of diversity in relation to where the responsibility to conduct an EIA lies, and to who bears the costs. For individual projects, it is more likely that a single organisation may be identifiable as the project sponsor, but one or more regulatory or oversight agencies may be involved, as may financial institutions. For larger-scale initiatives, joint ventures among multiple private sector organisations, and public-private partnerships, are more commonly involved, and the EIA may need to be performed or commissioned by, and perhaps largely funded by, the public purse.

During the same period as EIA, Technology Assessment (TA) emerged, as a careful analytical technique with a focus on one or more technologies, viewed as interventions into a particular, existing physical, social and/or economic context (OTA 1977, Garcia 1991). TA inherently reflects the needs of all parties involved. The techniques emerged with the US Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) 1972-1995, and European OTAs from the early-to-mid 1980s.

The establishment of the US OTA followed a period in which Rachel Carson's 'Silent Spring' had alerted the public to environmental impacts (in that case, to the insecticidal impacts of DDT) and Ralph Nader's 'Unsafe at Any Speed' had sounded the alarm bells about the design of cars. It was an organ of the US parliament, and reported to a Committee of Congress. During the 1990s, US politics changed. Economic factors gained dominance over social goals. Meanwhile,. the growth in size and power of corporations, and trans-nationalism, resulted in government and regulation being downgraded to governance and 'self-regulation'. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) became debased to Environmental Impact Statements (EIS). OTA was disestablished during the Reagan Administration, in 1995.

The notion of Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) emerged through the 1970s and 1980s. For example, a US report stated that "there is no vehicle for answering the question: "Should a particular record-keeping policy, practice, or system exist at all?" (PPSC 1977). Flaherty (1989) quotes a 1984 document of the Canadian Justice Committee which refers to a 'privacy impact statement' (p.277-278), and documents instances where pre-decisional assessments were occasionally used in some European countries such as the Scandinavian countries and the U.K. (p.405). In Australia, the Data-Matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 included in Schedule 1 a requirement for a 'program protocol'.

The earliest documentary evidence of the term PIA found to date is in a Berkeley, California ordinance reproduced in Hoffman (1973). The term was in use in Ontario and British Columbia through the 1990s. The first publications explaining the purpose and process appear to have been Stewart (1996a, 1996b) and Clarke (1998a, 1998b). The idea took longer to gain traction in Europe, but see Kenny & Borking (2002). The first guidance in a European country appears to have been in the UK (ICO 2007). Comprehensive background is provided by Clarke (2009) and Wright & de Hert (2012).

A recurrent challenge with PIA guidance has been the tendency of government agencies to quickly ratchet the requirements down, both from a business process to a mindless form-filling exercise, and from an open-ended assessment of consequences to a mere check of compliance with extant law. This has been evident throughout the USA, in most of Canada, and in the UK. In the case of the EU 'Data Protection Impact Assessment' (DPIA), on the other hand, the notion was neutered at birth (Clarke 2017).

Whereas PIAs have a focus on privacy interests (and, all too often, on a sub-set of them, usefully described as data privacy), Social Impact Assessment (SIA) adopts a much broader frame of reference. SIA is concerned with the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions (policies, programs, plans, projects), seeking a more sustainable and equitable bio-physical and human environment (Vanclay 2003, p. 6).

A more recent development has been the Human Rights Impact Assessment (HIA). "[HRIA is] an instrument for examining policies, legislation, programs and projects and identifying and measuring their effects on human rights. HRIAs provide a reasoned, supported and comprehensive answer to the question of 'how does the project, policy or intervention affect human rights?'" (World Bank 2013, p. 1). Key elements identified in that document are the use of a normative human rights framework as the reference point, public participation, equality and non-discrimination, transparency and access to information, accountability, an inter-sectoral approach and international policy coherence.

The notion has attracted attention not only in the developing world, but also in many developed countries. In Australia, however, HRIA is hamstrung in Australia by the failure of successive federal parliaments to fulfil their responsibility to implement comprehensive human rights protections, in accordance with the nation's accession to ICCPR: "Despite signing the ICCPR in 1972 and ratifying it in 1980, Australia has never adopted it into domestic law" (APH 2017).

A recently-published guide in relation to AI in banking is indicative of the problem (NAB/AHRC 2023). The document's scope and value are muted firstly by the absence of a normative human rights framework, and secondly by the dominance of a sponsor that is among the largest 10 Australian-listed corporations. It is designed as a means of avoiding regulation, enabling corporations to continue their activities with minimal disturbance. The notions of justification, proportionality, an obligation to provide humanly-understandable explanations for decisions, and a requirement to not conduct activities that unreasonably cause harm, are all avoided. Instead, the focus is entirely on accepting that the corporations' actions will give rise to harm, and giving vague consideration to ways to mitigate the damage caused.

The sponsor of an intervention generally takes their own self-interest into account, and hence thinks about the downside impacts and implications for that organisation. Other parties that may be affected by the intervention, on the other hand, are commonly in a less strong position to protect their interests. In business management theory, the term 'stakeholders' emerged as a counterpoint to 'shareholders' (Freeman and Reed, 1983, Laplume et al. 2008). A stakeholder is any organisation, group or individual affected by an activity. So-called 'stakeholder salience theory' distinguishes stakeholders on the basis of their power, legitimacy, and urgency (Mitchell et al. 1997). Many stakeholders are participants in the social system into which an intervention is introduced. In technosocial systems involving ICT, participants are commonly referred to as 'users'. The term 'usee' has emerged, to refer to additional, non-participating entities that very likely lack the power to affect a process and may even be unaware of it, but are nonetheless affected by it (Berleur & Drumm 1991 p.388, Clarke 1992, Fischer-Huebner & Lindskog 2001, Baumer 2015).

The practice of business case development has been such that the focus is squarely on the interests of the sponsor of the intervention, and hence the only stakeholders whose interests are likely to be treated as being of any relevance are those that have sufficient power to represent a threat to the achievement of the sponsor's objectives in implementing the intervention (Achterkamp & Vos 2008, (Ackermann & Eden 2011).

A further important consideration in this discussion is the range of ways in which organisations designing and implementing interventions may be subjected to influences that regulate their behaviour. This is usefully modelled as a hierarchy of regulatory mechanisms, as outlined in Figure 1, and examined in some depth in Clarke (2021, 2022).

(From Clarke 2021, Figure 2)

At the base Level (1), the model recognises the existence of natural constraints on behaviour, intrinsic to the particular social system, such as countervailing power by those affected by an initiative, activities by competitors, reputational effects, and cost/benefit trade-offs. Level (2) relates to infrastructural factors, such as ICT design features that automatically monitor and constrain behaviour. One popular expression for infrastructural regulation is '[US] West Coast Code', as distinguished from the East Coast Code (law) that is at the other extreme of Level (7), formal regulation (Lessig 1999, Hosein et al. 2003).

Statutes and formal codes have been augmented in recent years by proposals at Level (6), particularly for co-regulation (whereby a slim legislative framework is enacted, but details are delegated to a quasi-authority to negotiate or determine), and meta-regulation (in which an obligation is created on a category of organisations to self-regulate). Levels (3)-(5) contain the various forms of self-regulation, whose primary function is to hold off formal regulation by creating the appearance that effective protections exist.

The techniques in the various levels of regulation adopt different ways of resolving the tensions between the interests of the intervention-sponsor and those of stakeholders. The techniques feature different mixes of obligations and compliance, on the one hand, together with incentives to sponsors to recognise and reflect the interests of stakeholders in their designs and operational activities.

The remainder of this presentation considers a novel approach to integrating the interests of sponsor and stakeholders, by proposing a relatively modest imposition on how sponsors perform their evaluation of a proposed intervention, but with the prospect in view of achieving an expansion of the scope well beyond internal Business Case Development, in the direction of Impact Assessment.

Historically, and still in contemporary practice in business and government, many sponsors of interventions do not conduct a single, comprehensive evaluation of a proposal. The most common approach is to first develop a Business Case, perhaps augmented by some more exacting process such as Net Present Value Analysis. This takes into account the kinds of benefits and costs that are apparent and capable of being estimated, or at least gauged or described. A further study may then be undertaken of contingencies that may affect the achievability of the anticipated net benefits. This has its focus on contingent risks of a financial, operational, reputational, compliance or strategic nature.

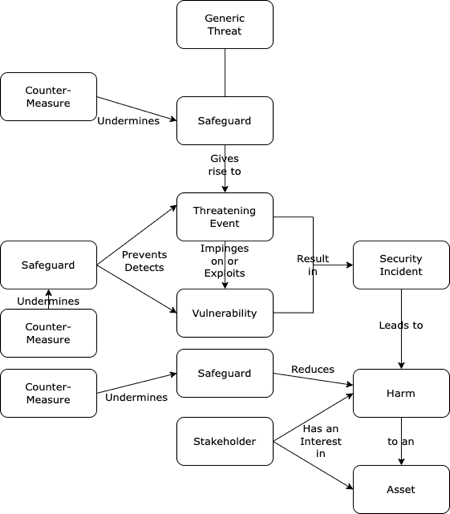

There are many sources of guidance in relation to organisational risk assessment and management. The techniques are particularly well-developed in the context of the security of IT assets and digital data, although the language and the approaches vary considerably among the many sources (e.g. NIST 2012, ENISA 2016, ISM 2023). For the present purpose, a previously-published depiction of the conventional security model is adopted (Clarke 2015, 2019). See Figure 2. The model culminates in a definition of Risk as the residual likelihood of occurrence of Harm arising to an Asset as a result of a Threatening Event impinging on a Vulnerability.

With one exception, all features in Figure 2 can be found in all of the primary sources. The exception is the inclusion at the bottom of the diagram of a role for Stakeholders, whose perspectives on Assets, and Harm to Assets, may vary considerably among stakeholders, and in comparison with the views of the intervention's sponsor.

(After Clarke 2015 Appendix 1, 2019 Figure 1)

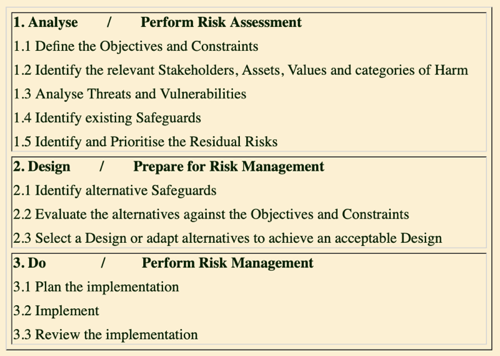

Applying the framework provided by Figure 2, the conventional approach to risk assessment and risk management is outlined in Figure 3. Relevant organisational assets are identified, and an analysis is undertaken of the various forms of harm that could arise to those assets as a result of threats impinging on or actively exploiting vulnerabilities, and giving rise to threatening incidents. Existing safeguards are taken into account, in order to guide the development of a strategy and plan to refine and extend the safeguards. A degree of protection is sought that is judged to suitably balance modest actual costs against potentially much higher but contingent costs.

(From Clarke 2019 Table 1)

The Risk Assessment process has a strong focus on the interests of the sponsor, with a heavy emphasis on the economic dimension, variously in the short-term (investment, operation and compliance) and the longer term (reputation and strategy). As noted earlier, consideration is generally given to the interests of any particular Stakeholder only if they are perceived to have sufficient Power that they represent a material risk to the achievement of the benefits or the management of the costs.

The following section examines the scope for adapting the well-established and well-understood business process of Risk Management to reflect the interests of not only the sponsor of the intervention, but Stakeholders as well.

In the specific context of Artificial Intelligence (AI), it has been argued (Clarke 2019, p.413, Michael, Abbas et al. 2021), that:

It has been further argued in Clarke et al. (2022) that those assertions apply not only to applications of AI, but extend to all schemes that have substantial IT-based components, and more generally to all interventions into sociotechnical and social systems.

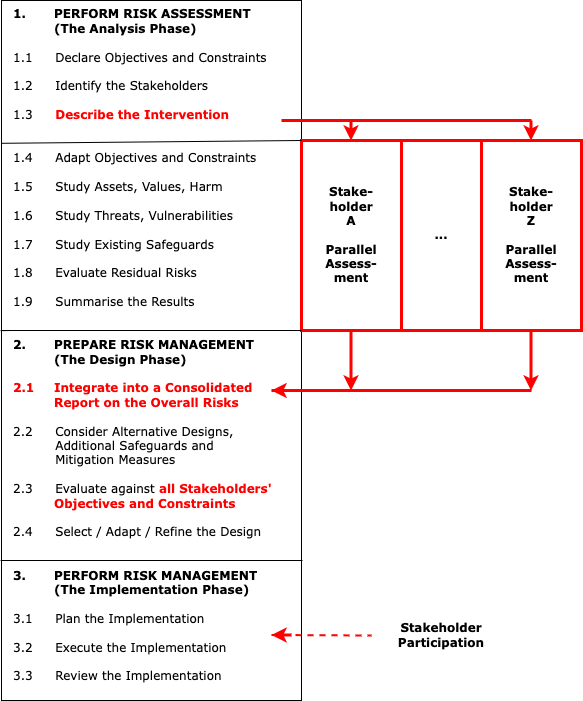

RA is capable of adaptation to accommodate stakeholders additional to the system sponsor, in the manner depicted in Figure 4, and referred to here as Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA). MSRA extends the conventional, organisation-internal RA process to encompass multiple, parallel assessments, all of which draw on a common base of information, but each of which is undertaken from the perspective of a particular stakeholder. The results of the various assessments are then integrated into a consolidated multi-perspective form. That integrated body of understanding is then applied during the Risk Management phases of the process.

(From Clarke et al. 2022)

There are of course practical challenges to overcome in implementing MSRA. There is considerable asymmetry of information, resources and power among stakeholders. Substantial disparity exists among stakeholders' perspectives, values and dialects. Few organisations' executives, analysts and designers are likely to be able to meet the challenges involved. Conventional project development techniques certainly are not. Each of the parallel activities requires information, and adequate human resources with the relevant expertise. The outcomes of the parallel studies then need to be interwoven, and that is an activity that is inevitably heavily political in nature. Preliminary experiments in MSRA's application do, however, give cause for optimism.

The MSRA technique has the effect of shifting the RA process beyond its limited, single-organisational scope, and absorbing some aspects of the broader, public policy orientation of Impact Assessment categories of evaluation techniques. It is nowhere near a 'half-way house' between the two families of business case and IA evaluation methods; but it may assist in bridging the yawning gap. So a possibility exists to achieve some limited protections for stakeholder interests during the wild frontier phase of technology-based entrepreneurism.

Achterkamp M.C. & Vos J.F.J. (2008) 'Investigating the use of the stakeholder notion in project management literature, a meta-analysis' Int'l J. Project Management 26, 7 (October 2008) 749-757

Ackermann F. & Eden C. (2011) 'Strategic management of stakeholders: Theory and practice' Long range planning 44,3 (2011) pp.179-196, at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Colin-Eden/publication/222804628_Strategic_Management_of_Stakeholders_Theory_and_Practice/links/56fe476908ae1408e15cfc05/Strategic-Management-of-Stakeholders-Theory-and-Practice.pdf

APH (2017) 'International Human Rights Law' Interim Report, Inquiry into the status of the human right to freedom of religion or belief, Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Australian Parliament, November 2017, at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Freedomofreligion/Interim_Report/section

Baumer E.P.S. (2015) 'Usees' Proc. 33rd Annual ACM Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI'15), April 2015, at https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2702123.2702147

Berleur J. & Drumm J. (Eds.) (1991) 'Information Technology Assessment' Proc. 4th IFIP-TC9 International Conference on Human Choice and Computers, Dublin, July 8-12, 1990, Elsevier Science Publishers (North-Holland), 1991

CFREU (2010) 'Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union' Official Journal of the European Union C83, pp. 389-403, 30 March 2010, at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:083:0389:0403:en:PDF

Clarke R. (1992) 'Extra-Organisational Systems: A Challenge to the Software Engineering Paradigm' Proc. IFIP World Congress, Madrid, September 1992, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/PaperExtraOrgSys.html

Clarke R. (1998a) 'Privacy Impact Assessments', Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 1998, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIA.html

Clarke R. (1998b) 'Privacy Impact Assessments', Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 1998, at http://www.xamax.com.au/DV/PIA.html

Clarke R. (2008) 'Business Cases for Privacy-Enhancing Technologies' Chapter 7 in Subramanian R. (Ed.) 'Computer Security, Privacy and Politics: Current Issues, Challenges and Solutions' IDEA Group, 2008, pp. 135-155, Republished as Chapter 3.15 in Lee I. (Ed.) 'Electronic Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications' (4 Volumes), IDEA Group, 2008, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/PETsBusCase.html

Clarke R. (2009) 'Privacy Impact Assessment: Its Origins and Development' Computer Law & Security Review 25, 2 (April 2009) 123-135, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAHist-08.html

Clarke R. (2011) 'An Evaluation of Privacy Impact Assessment Guidance Documents' International Data Privacy Law 1, 2 (March 2011), PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAG-Eval.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'Approaches to Impact Assessment' Notes for a Panel Presentation at CPDP'14, Brussels, 22 January 2014, on the topic of 'Legal and Non-Legal Technology Impact Assessments', at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/IA-1401.html

Clarke R. (2015) 'The Prospects of Easier Security for SMEs and Consumers' Computer Law & Security Review 31, 4 (August 2015) 538-552, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/SSACS.html

Clarke R. (2017) ''The Distinction between a PIA and a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) under the EU GDPR' Notes for a Panel at CPDP, Brussels, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, January 2017, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAvsDPIA.html

Clarke R. (2019) 'Principles and Business Processes for Responsible AI' Computer Law & Security Review 35, 4 (2019) 410-422, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/AIP.html

Clarke R. (2021) 'A Comprehensive Framework for Regulatory Regimes as a Basis for Effective Privacy Protection' Proc. 14th Computers, Privacy and Data Protection Conference (CPDP'21), PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/RMPP.html

Clarke R. (2022) 'Research Opportunities in the Regulatory Aspects of Electronic Markets' Electronic Markets 32, 1 (Jan-Mar 2022) 179-200, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/RAEM.html

Clarke R. & Davison R.M. (2020) 'Through Whose Eyes? The Critical Concept of Researcher Perspective' J. Assoc. Infor. Syst. 21, 2 (March-April 2020) 483-501, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/RP.html

Clarke R., Michael K. & Abbas R. (2022) 'Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment of Socio-Technical Interventions' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2022, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/MSRA.html

Dikov D. (2020) 'Using the Net Present Value (NPV) in Financial Analysis' Magnimetrics, 2020, at https://magnimetrics.com/net-present-value-npv-in-financial-analysis/

Elkington J. (1994) 'Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development' California Management Review 36,2 (1994) 90-100

ENISA (2016) 'Risk Management: Implementation principles and Inventories for Risk Management/Risk Assessment methods and tools' European Union Agency for Network and Information Security, June 2016, at https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/risk-management-principles-and-inventories-for-risk-management-risk-assessment-methods-and-tools

Fischer-Huebner S. & Lindskog H. (2001) 'Teaching Privacy-Enhancing Technologies' Proc. IFIP WG 11.8 2nd World Conf. on Information Security Education, Perth, Australia, 2001

Flaherty D. (1989) 'Protecting Privacy in Surveillance Societies' Uni. of North Carolina Press, 1989

Freeman R.E. & Reed D.L. (1983) 'Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance' California Management Review 25, 3 (1983) 88-106

Hedman J. & Henningsson S. (2016) 'Developing Ecological Sustainability: A Green IS Response Model' Information Systems Journal 26,3 (2016) 259-287

Hoffman L. (1973) 'Security and Privacy in Computer Systems' Melville Publishing Co., Los Angeles, California, 1973

Hosein G., Tsavios P. & Whitley E. (2003) 'Regulating Architecture and Architectures of Regulation: Contributions from Information Systems' International Review of Law, Computers and Technology 17, 1 (2003) 85-98

IAIA (2009) 'What Is Impact Assessment?' International Association of Impact Assessment (IAIA), October 2009, at https://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/What_is_IA_web.pdf

ICO (2007) 'Privacy Impact Assessment Handbook' Information Commissioner's Office, Wilmslow, I.K., December 2007, archived copy at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAHbk-v1.0.pdf

ISM (2023) 'Information Security Manual' Australian Signals Directorate, December 2023, at https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/ism

Lessig L. (1999) 'Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace' Basic Books, 1999

Kenny S. & Borking J. (2002) 'The Value of Privacy Engineering' The Journal of Information, Law and Technology (JILT) 2002 (1), at http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/law/elj/jilt/2002_1/kenny/

Laplume A.O., Sonpar K. & Litz R.A. (2008) 'Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us' Journal of Management 34,6 (2008) 1152-1189

Milne M.J. & Gray R. (2013) 'W(h)ither Ecology? The Triple Bottom Line, the Global Reporting Initiative, and Corporate Sustainability Reporting' Journal of Business Ethics 118,1 (2013) 13-29

Mitchell R.K., Agle B.R. & Wood D.J. (1997) 'Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts' Academy of Management Review 22,4 (1997) 853-886

Morgan R.K. (2012) 'Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art' Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30,1 (2012), at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14615517.2012.661557

NAB/AHRC (2023) 'Human Rights Impact Assessment Tool: AI-informed Decision-making Systems in Banking' NAB / Australian Human Rights Commission, September 2023, at https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/ai_in_banking_hria_tool.pdf

NIST (2012) 'Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments' US National Institute for Standards and Technology, SP 800-30 Rev. 1 Sept. 2012, pp. 23-36, at https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-30/rev-1/final

PPSC (1977) 'Personal Privacy in an information Society' Privacy Protection Study Commission, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., July 1977, at http://epic.org/privacy/ppsc1977report/, http://aspe.hhs.gov/datacncl/1977privacy/toc.htm

Schmidt M.J. (2005) 'Business Case Essentials: A Guide to Structure and Content' Solution Matrix , 2005, at http://www.solutionmatrix.de/downloads/Business_Case_Essentials.pdf

SoW (2013) 'Discounted Cash Flow Analysis' Street of Walls, 2013, at https://www.streetofwalls.com/finance-training-courses/investment-banking-technical-training/discounted-cash-flow-analysis/

Stewart B. (1996a) 'Privacy impact assessments' Privacy Law & Policy Reporter 3, 4 (July 1996) 61-64, at http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/disp.pl/au/journals/PLPR/1996/39.html

Stewart B. (1996b) 'PIAs - an early warning system' Privacy Law & Policy Reporter 3, 7 (October/November 1996) 134-138, at http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/disp.pl/au/journals/PLPR/1996/65.html

Stobierski T. (2019) 'How To Do a Cost-Benefit Analysis & Why It's Important' Harvard Business School Online, September 2019, at https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/cost-benefit-analysis

Vanclay F. (2003) 'International principles for social impact assessment' Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 21,1 (March 2003) 5?12, at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.3152/147154603781766491

World Bank (2013) 'Human rights impact assessments: a review of the literature, differences with other forms of assessments and relevance for development' World Bank, Washington DC, at https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/834611524474505865/pdf/125557-WP-PUBLIC-HRIA-Web.pdf

Wright D. & De Hert P. (eds) (2012) 'Privacy Impact Assessments' Springer, 2012

This presentation draws heavily on, and extends, multiple previous publications and presentations by the author and in some cases co-authors. The contributions are acknowledged of those co-authors, of informal reviewers and seminar participants, and of formal reviewers and editors of the publisher papers.

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professorial Fellow associated with the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation in UNSW Law, and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 18 February 2024 - Last Amended: 19 February 2024 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/DV/IAA24.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy