Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Working Paper Revision of 15 July 2019

Developed in the context of the

Consumers

International Summit and ISOC Meetings,

Estoril PT, 29 April - 1 May

2019

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2019

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/IoTCP.html

The Internet of Things (IoT) is widely assumed to offer a great deal of promise to organisations and individuals. It also harbours enormous threats to consumers. Consumer advocacy organisations, and some consumers, are awake to the risks, and are actively seeking ways to achieve effective management of the consumer downsides and risks. A framework is needed within which suitable initiatives can be identified and evaluated. This document draws on many sources in order to propose such a framework.

The IoT field is highly diverse, and the first necessary step is to define a set of segments, each of whose upsides, downsides and risks are sufficiently uniform that safeguards can be devised.

The challenges to consumers' interests are then outlined in four groups: commercial, security, the physical self and data. The challenges need to be examined in greater depth in respect of each IoT segment.

Alternative approaches to regulation are outlined, and applied to IoT.

Conventional approaches to achieving regulatory reform are identified, and three key alternative initiatives are outlined: an assessment program for IoT devices and systems, consolidation of authoritative checklists, and consumer-issued Standards.

The Internet of Things (IoT) has been argued to create enormous opportunities. Many devices and applications are directly targeted at consumers, and many others have potential for consumer benefits. There is ample scope for organisations to make those benefits appear highly attractive to consumers. However, IoT brings with it many new disbenefits and challenges for consumers and exacerbates many existing problems.

These notes provide short summaries of key aspects of IoT relevant to the protection of consumer interests. A major re-alignment of consumer protection practices and laws is necessary. The purpose of these notes is to lay a sufficient foundation for discussion of the actions that consumer advocacy organisations can take in order to achieve

The next section addresses the question of what IoT is and may be. Because it has many forms, exhibits many attributes, and is capable of application in many contexts, it is necessary to segment the industry in order to make sense of the challenges and the possible initiatives to address them.

The next section after that identifies the wide range of challenges to consumers' interests. These are divided into commercial and security concerns, followed by separate treatment of threats to the physical self and to personal data.

A brief summary is provided of key features of existing regulatory regimes, in order to identify alternative approaches that can be taken to the problems. This enables discussion of the activities that consumer advocacy organisations may need to undertake, in order to stimulate action by relevant institutions, to provide general form to that action, and to guide and influence the specific formulations of regulatory instruments.

During the period c. 1980-2010, inter-connection among computers gradually became effective, inexpensive and commonplace. From perhaps 2030 onwards, inter-connectedness may be similarly commonplace for a wide range of artefacts. During the current, transitional phase, the term IoT is being applied to artefacts that originally lacked communications capabilities and that were not perceived as needing them. Hence ISOC refers to "scenarios where network connectivity and computing capability extends to objects, sensors and everyday items not normally considered computers, allowing these devices to generate, exchange and consume data with minimal human intervention" (ISOC 2015). Other informal definitions of an IoT device include "a physical object that connects to the Internet. It can be a fitness tracker, a thermostat, a lock or appliance - even a light bulb" (OTA 2017) and "a generic term describing the practice of adding internet-connected sensors and controllers to objects, infrastructure or locations, and using the data ..." (DoCA 2018). The following definition has as its focus consumer-related forms of IoT, and was used during the conduct of a recent survey of consumers: "everyday products and devices that can connect to the Internet using Wi-Fi or Bluetooth, such as connected meters, fitness monitors, connected toys, home assistants or gaming consoles ... [excluding] tablets, mobile phones and laptops" (CI/ISOC 2019).

However, the term 'IoT' is misleading. Although inter-connection is a defining characteristic, this does not need to be achieved by means of the Internet - which necessarily implies use of the Internet Protocol (IP) and either the TCP or the UDP protocol. In fact, many 'IoT' devices lack the capacity to achieve Internet-connection, and communicate with other devices using channels and protocols that involve lower overheads than UDP/IP, such as Zigbee.

In Manwaring & Clarke (2015), the diverse elements and attributes are identified, not only of IoT but also of the earlier, related notions of ubiquitous and pervasive computing and ambient intelligence. Those authors use the term 'eObject' to refer to "an object that is not inherently computerised, but into which has been embedded one or more computer processors with data-collection, data-handling and data communication capabilities". In addition to the core attributes, an eObject may have any combination of a substantial number of additional atttributes. Important among these are prevalence, locatability in network space and in physical space, mobility within both kinds of space, identifiability, associability with a living being, and the ability to take actions that affect the physical world.

Given the enormous range of technologies, contexts and uses, broad conceptions such as IoT and eObjects need to be segmented into categories each of which exhibits enough commonality that useful generalisations can be made about their nature, benefits, disbenefits, harm, risks and safeguards. In devising IoT segments, the attributes identified by Manwaring & Clarke (2015) are relevant, but the nature of the association with individual consumers needs careful consideration. Table 1 suggests a pragmatic approach to IoT segmentation.

It is conventional to recognise that 'IoT is different'. It is important, however, to move beyond vague feelings and assertions, and identify (a) specific ways in which IoT is different, and (b) how those differences create new problems or exacerbate existing problems.

Some technological challenges are inherited from computing technologies generally, while others arise from weaknesses of wireless communications. Some problems are exacerbated, e.g. the small size of mobile eObjects limits the energy available and hence the length of time they can operate untethered and the speed with which batteries can be re-charged, limits the processing power and hence cryptographic computations and data transmission speeds, limits the storage space, and limits the scope for interactivity with users.

Some technological challenges are, on the other hand, different from many other forms of IT. Much of the IT industry operates in supply-chain form, with a degree of stability in relationships, often for extended periods of time. The IoT industry, on the other hand, tends towards network forms rather than linear chains, and the participation of suppliers is more fluid. Associated with this fluidity, and with the limited capacity of IoT devices, is a casualness among technology providers in relation to quality, reliability and longevity. A security audit or a review of supply reliability may be rapidly undermined by change. Unpredictable vulnerabilities arise, and there is much higher risk of service failure arising from imperfect substitutability of service-providers.

Further difficulties arise from the depedence of IoT devices' functionality on supporting infrastructure. Unit-testing addresses the behaviour of IoT devices either in isolation from that infrastructure, or in the presence of just one or a few specific instances of that infrastructure. Considerable challenges arise in relation to the reviewability, auditability and certifiability even of individual IoT devices, but even more so in relation to systems that include IoT devices.

This section contributes to the process of teasing out the differences and their consequences, by distinguishing several categories of challenge. The first group addressed below is concerned with consumers' associations with suppliers, the second with technical aspects of security, the third with impacts on the physical self, and the fourth with impacts on personal data. The final sub-section considers the interplay between the IoT segments noted in Table 1 and the four categories of challenge to consumers' interests.

Consumers' commercial interests have needed protection since long before the emergence of even eCommerce, let alone IoT. As reported in Manwaring (2017), the 2015-16 revision of the UN's Guidelines for Consumer Protection' (UNGCP 2016) defines "the main characteristics of effective consumer protection legislation, enforcement institutions and redress systems" as being:

The spread of web-commerce and the broader eCommerce fields since the 1990s brought with it new and expanded forms of threat (Clarke 2006, Clarke 2008, Svantesson & Clarke 2010). A categorisation of these generic challenges is in Appendix 1. [If a categorisation is found that is widely-adopted and authoritative, and at least as comprehensive as that in Appendix 1, substitute it.]

The nature of IoT technologies and IoT industry-structure gives rise to substantial further difficulties for consumers and exacerbates many existing issues. Root causes of challenges to consumers' commercial interests include inadequacies of eObjects, insufficient attention by designers to consumer needs, the information and power asymmetry between consumers and providers, the networked nature of industry structures, and the many weaknesses of contract law as a means of protecting consumers including the doctrine of privity of contract. Table 2 draws in particular on Manwaring (2017) and CI (2017).

Security issues have been a feature of interconnected computers since the emergence of networking (Clarke & Wigan 2018). Organisations of all sizes are afflicted, but the kinds of devices used by consumers and small business have proven to be especially difficult to protect (Clarke 2015). The advent of IoT is compounding these existing challenges (Cisco 2016, CI 2017). The additional and exacerbated problems derive from a number of features of IoT, in particular:

The term security is used to refer to an enormous range of circumstances, needs and issues. To avoid ambiguities and confusions it is valuable to impose some structure.

A conventional model of security exists. It embodies a set of inter-related terms that are capable of sufficiently clear definition that ambiguities and confusions can be avoided, and reliable analysis and discussion of problems and solutions can be undertaken (CC 2012, Firesmith 2004, IETF 2007, ISO 2012). A graphical representation is provided in Figure 1, and definitions of the terms are provided in Appendix 1 to Clarke (2015).

Extract from Appendix 1 to (Clarke 2015)

All parties in the game have their own aims to pursue, but the interests of concern here are those of consumers.

Incidents that may give rise to harm to consumers' interests can be usefully classified into the following groups:

Consumers have interests in a variety of assets and values. Those relevant in the context of IoT are:

Adapted version of Clarke (2010b)

____________

The various types of threats need to be countered by technical safeguards.

As regards devices used by consumers generally, an 'absolute-minimum' set of security safeguards is outlined in Appendix 2. Further detail is provided in Appendices 2-4 of Clarke (2015), which list baseline, additional and more advanced security features that devices may need, depending on their nature and context of use.

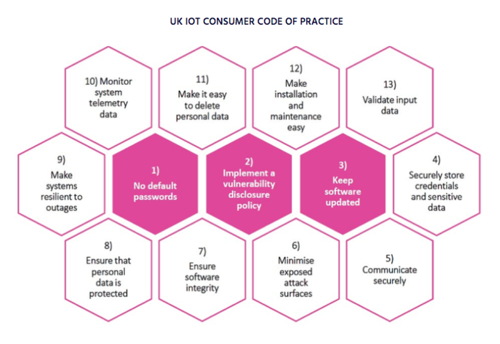

In relation to IoT specifically, a limited set of "minimum standards" is listed in CI/Mozilla/ISOC (2018). Other guidelines are in IoTA (2018) and UK (2018). For a more substantial industry publication, see IoTSF (2018).

In order to address the security challenges that IoT poses to consumers, appropriate activities need to be conducted during the design and implementation phases of systems. An outline of risk assessment and risk management processes is in Appendix 3. An outline of generic risk management strategies is in Appendix 4.

However, risk assessment and management processes were devised in order to protect the interests of organisations, and such benefits as arise to consumers are incidental rather than the primary purpose. For consumer interests to be adequately protected, either risk assessment and management processes must be adapted in order to serve the need (e.g. Clarke 2019b), or alternative processes need to be adopted that prioritise the needs of the affected public, such as technology assessment or impact assessment (Clarke 2014).

IoT-based services can have both direct and indirect impacts on consumers' self-determination, discrimination against them, bodily integrity and personal safety.

Self-determination is undermined where other parties gain access to and utilise personal data in such a way as to manipulate a consumer's behaviour. A common approach is to structure and time offers to an individual in ways that are calculated to be sufficiently attractive that the individual takes actions that are not in their own best interest. During the last decade, a particular business model has emerged, and rapidly become dominant, which has given rise to the 'digital surveillance economy' (Clarke 2019a) and 'surveillance capitalism' (Zuboff 2019).

Fitness trackers and devices and services that offer 'wellness' can be designed to as to induce or embarrass individuals to, or not to, behave in particular ways. Meanwhile, many features of 'smart vehicles' (e.g. monitoring by insurers), 'smart neighbourhoods' (e.g. energy-usage monitoring, and vigilantism), and 'smart cities' (social control), are designed to benefit parties other than individual consumers, and to serve values that may even be diametrically opposed to those of individual consumers. The surveillance that is inherent in many IoT applications enables the exercise of power over individuals. Moreover, the mere belief that surveillance takes place is enough to curb individuals' behaviour, because of 'the chilling effect' - the voluntary avoidance of particular behaviour because of a generalised fear of retribution by some powerful authority.

A further risk is more extensive and intensive discrimination. The increasing denial of anonymity, and collection by service-providers of substantial amounts of personal data, both directly and from other sources, greatly increases the scope for discrimination against the interests of consumers. IoT also greatly increases the scope for service denial on the basis of previous behaviour, as is being pioneered at national level in China's 'social credit' scheme (Chen & Cheung 2017, Liang et al. 2018).

Bodily integrity is under threat where devices that are embedded within individuals take actions, such as adapting neural inputs (in the case of cochlear and retinal implants), generating electrical impulses (in the case of heart pacemakers), or injecting chemicals into the bloodstream (in the case of, for example, an 'intelligent' insulin pump). In each of these cases, the capability of such devices to offer considerable benefits to individuals is well-established. Risks exist, however, such as malfunction, badly-implemented updates, external interference, and co-option for purposes other than the individual's well-being.

The location and tracking of identified individuals gives rise to risks to some individuals from other individuals and from organisations that have an interest in harming them, limiting their movement, or otherwise constraining their liberty. In addition, consumers' personal safety is threatened by autonomous vehicles. These are dependent on real-time data-gathering, communication and analysis, and their design may be much less effective and much more error-prone than their proponents claim.

Consumers have embraced some applications of IoT. However, even those that meet a consumer need, and that are exciting, are giving rise to considerable unease about data collection, retention, use and disclosure (CI 2017, CI/ISOC 2019).

In Xaver et al. (2016), four privacy themes are identified that arise from IoT:

In Madaan et al. (2018) a further factor is identified: the considerably increased threat-level to individuals arising from the linkage of data streams from many more sources than has previously been the case. For a suite of technical safeguards for data in IoT contexts, see IoTAA (2017).

The term 'IoT' encompasses a very wide range of devices and services. In Table 1, an approach to IoT segmentation was proposed, in order to provide a basis for assessing risks and devising safeguards. However, technologies and their applications are only one dimension. Other considerations need to be factored in as well. Relevant factors for consumer segmentation include the individual's tendency to risk-aversion, degree of enthusiasm for technological innovation, and loyalty, but also socio-economic factors, educational level, and vulnerability. A further dimension arises from the sensitivity of the data that is handled, with differentiation necessary among, for example, location, tracking, financial data and health data

Different consumer segments have different needs, and those needs cannot be served unless IoT devices and IoT-based services embody design features that reflect the differences and are adaptive to individuals' needs. Some consumers are likely to exhibit significant dependence on some IoT-based systems. Hence children's toys, adult entertainment, navigation, home-hubs, wellness-monitoring and active health-intervention uses need to be subject to radically different quality assurance regimes, safeguards and mitigation measures. An example of an initiative in a specific context is Consumer International's 'Checklist for retailers of connected products and services marketed to children or for children' (CI 2019).

Safeguards need to be devised and implemented that reflect not only the technical characteristics of the IoT devices and the services based on them, but also the needs of the various categories of consumers who use them. The necessary protective measures therefore vary markedly depending on the context.

Regulation encompasses many forms, including law, but also mechanisms variously of an organisational, economic and technical nature. This section first provides an overview of the available options, drawing in particular on Gunningham et al. (1998), Braithwaite & Drahos(2000) and Drahos (2017), and then considers the extent to which they appear to be applicable to IoT.

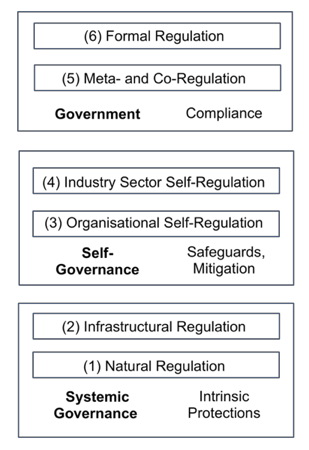

The notion of 'regulation' is far broader than that of 'law'. It is useful to regard regulatory mechanisms as existing in a hierarchy, as depicted in Figure 2. Most successful regulatory schemes involve elements from two or more of the six levels.

Extract from (Clarke 2019b)

The bottom-most layer of the hierarchy is (1) Natural Regulation. By this is meant that artefacts and systems may be subject to limitations as a result of processes that are intrinsic to the relevant socio-economic system. Technologies may not be able to deliver on their promises, or may depend on infrastructure that is unreliable, or may be too expensive. Alternatively, the innovation may be stifled by powerful market or institutional forces. These may include reputational effects, whereby public opinion, influenced and transmitted by the media and by social media, may undermine the technology's standing. A threshold test needs to be applied: are the natural controls sufficient by themselves, or do they need to be supplemented by additional measures?

The second-lowest layer in the hierarchy, (2) Infrastructural Regulation, comprises features of the socio-technical system whose effect is to encourage beneficial behaviour and prevent or at least discourage harmful behaviour. A popular expression for infrastructural regulation is 'West Coast Code' (Lessig 1999). This refers to features of the standards and protocols that define computer and network architecture, and functions of hardware and software infrastructure. Data security measures, detection of battery-failure, and self-reporting of defects, are examples of infrastructural regulation.

Suppliers of IoT devices and systems may implement layer (3) Organisational Self-Regulation. This may be done by means of internal codes of conduct and 'customer charters', and through self-restraint associated with 'business ethics' and 'corporate social responsibility'. In practice, however, organisational self-regulation is almost always ineffectual from the viewpoint of the supposed beneficiaries, and often not even effective at protecting the organisation itself from bad publicity.

Corporations club together for various reasons, some of which can be to the detriment of other parties, such as collusion on bidding and pricing. Industry associations can, however, deliver significant benefits for consumers, in particular where collaborative approaches to infrastructure improve services, reduce costs, and even embed infrastructural regulatory mechanisms. Associations may also implement the next layer, (4) Industry Self-Regulation, through codes of conduct and 'trust marks'. However, few such arrangements are sufficiently stringent to protect consumer interests, and the absence of enforcement undermines the endeavour. Such schemes more commonly act as camouflage, obscuring the absence of safeguards and holding off actual regulatory measures.

The uppermost layer of the regulatory hierarchy, (6) Formal Regulation, exercises the power of a parliament through statutes. Laws demand compliance with requirements that are expressed in reasonably specific terms. They need to be complemented by sanctions and enforcement powers. Lessig underlined the distinction between infrastructural and legal measures by referring to formal regulation as 'East Coast code'. However, statutory processes are slow, are heavily influenced by economically powerful organisations, commonly result in compromises that are unworkable, and are inflexible, with even seemingly small changes taking many years to achieve passage.

Intermediate forms have emerged, usefully referred to as (5) Meta-Regulation and Co-Regulation. Meta-regulation involves the parliament formally requiring an industry to exercise self-regulation. Co-regulation, on the other hand, features legislation that establishes a regulatory framework but carefully delegates the details. Key elements are authority, obligations, general principles that the regulatory scheme is to satify, sanctions and enforcement mechanisms. The detailed obligations are developed through consultative processes among advocates for stakeholders. The result is an enforceable Code, which articulates, and must be consistent with, the general principles expressed in the relevant legislation. The participants necessarily include at least the regulatory agency, the regulatees and the intended beneficiaries of the regulation, and the process must reflect the needs of all parties, rather than being distorted by institutional and market power. Meaningful sanctions, and enforcement of them, are intrinsic elements of a scheme of this nature. Unfortunately, from the consumer perspective, almost all instances of meta-regulation to date have been failures, and few good exemplars of co-regulation can be found.

IoT is in one sense merely another form of IT. Regulatory schemes have matured to some degree to accommodate IT, although serious difficulties remain, depicted as the 'digital surveillance economy' (Clarke 2019a) and more broadly as 'surveillance capitalism' (Zuboff 2019). Moreover, IoT embodies some features that undermine such regulatory arrangements as do exist. As discussed in section 3, these include complex supplier networks, transient providers, relatively simple and hence unreliable and insecure devices and systems, unenforceable contracts, and sensitive data.

Existing regulatory arrangements appear highly unlikely to be capable of protecting consumers against either technological errors and failures or corporate misbehaviour. Calls have been made for significant further developments in consumer protections (CI 2017).

In relation to security, there has been some relevant activity within standards organisations, e.g. internationally in relation to vulnerability disclosure (ISO 2018), and in the USA with the release of a discussion document (NIST 2019). A nominal requirement for "reasonable security features" is in force in California with effect from 1 January 2020 (Cal 2018), although the vagueness of the provisions, combined with built-in loopholes and the absence of a private right of action are such that it appears likely to have very limited impact. The UK government has published a soft guidance document (UK 2018), and the relevant UK Minister has floated the possibility of some (largely tokenist) statutory requirements in relation to a small number of security features.

Given their visceral nature, medical implants are an area in which it could be expected that positive exemplars of regulatory activity would be found. Some relevant International Standards exist, such as ISO (2011), and regulators such as the US Feed & Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) have protocols in place in relation to the design and testing of the functionality, reliability, robustness and resilience of devices that are intended for embedment in humans. In the EU, there is a longstanding Directive 90/385/EEC on active implantable medical devices (AIMDD). On the other hand, studies conducted by investigative journalists and published in reputable media outlets have thrown considerable doubt on the effectiveness of these processes in protecting consumers' interests (ICIJ 2019).

The general inadequacy of organisational and industry self-regulation is highly likely to apply to IoT, because of the absence of incentives, and the lack of interest of parliaments and regulators in exercising control over technological innovation. Similarly, 'trust marks', which are most appropriately thought of as 'meta-brands' (Clarke 2001), offer little prospect of having any significant impact, particularly in the absence of Standards and of any 'meta-brand provider' likely to achieve and sustain trustworthiness. At least during the early decades of IoT, the scope for 'infrastructural regulation' also appears to be limited, because of the limited capacity of the devices and the lack of incentive.

In short, apart from formal regulation, the only other approach that appears likely to deliver consumers' needs is co-regulation. Given the substantial risks inherent in IoT, which are not just theoretical, nor merely latent, but are already in evidence, there is a strong argument for application of the precautionary principle, i.e. regulation in advance of development and deployment.

Regulatory reform does not happen unless it is driven by some institution and/or circumstances. Table 4 identifies ways in which civil society encourages and may even drive changes to the law. The techniques are of value, but seldom deliver all that consumers need. The market and institutional power of consumer advocacy organisations is rarely adequate to dictate change, or even to provide a decisive nudge at a 'tipping-point' time.

Publications documenting and analysing concerns

Engagement with industry:

Engagement with channels for regulatory change:

Influence on formative documents:

Opportunistic Anouncements:

The mechanisms identified in the preceding section are often inadequate to satisfy consumers' needs. The challenges are all the greater where the proponents of a new technology succeed in conveying to policy-makers and the media promises of exciting new possibilities and the need to suspend the imposition of controls in order to enable the new industries to flourish. This section identifies several additional, linked avenues that consumer advocacy organisations can use in order to address the risks of rampant technological determinism and achieve protections for consumer interests.

It is important that information be made available about the characteristics of consumer-relevant IoT devices and systems. The first sub-section proposes that consumer advocacy organisations fulfil that need, by applying their established expertise to the evaluation of key examples of IoT, and publishing and promoting the resulting reports.

In order to perform assessments with the necessary professionalism, it is necessary to have norms against which products and services can be checked. The second sub-section proposes that consumer advocacy organisations have an important role to play in establishing and maintaining sets of requirements or principles.

Documents of this nature need to be provided with the aura of authority. The third sub-section proposes that the publication mechanism be formalised, in order to produce Consumers Standards, published by an appropriately-named organisation, e.g. Consumers International Standards Organisation (CISO). These would contain requirements statements that stand alongside the technical specifications published by ISO as Industry Standards.

A material contribution to preparedness to undertake change can be made by evaluating individual goods and services, and publishing the results. Desirably, some publications would be of the nature of case studies of responsible design and deployment. Given the history to date, however, it is likely that most evaluations would result in warnings about products, and that some proportion of evaluations would result in additions to a 'rogues gallery'.

A range of consumer advocacy organisations already conduct assessment programs for a wide range of consumer goods and services, and the scope of those programs could be expanded. Alternatively, if it is judged that suppliers whose products are severely criticised might hit back, e.g. through legal threats, a possibility would be to decentralise the evaluation process and publish on a public wiki rather than on consumer advocacy organisations' own sites. In either case, however, it is essential that the evaluation process be performed in a sufficiently professional manner, and that the process and product be transparent.

The 'rogues gallery' could be bootstrapped by curating a collection of early failures, as documented in the media - qualified of course by a statement of the manner in which those evaluations were conducted, and drawing attention to any evident shortfalls in the processes and checklists used.

The objectives of such an undertaking would be:

Some aspects of such evaluations could be conducted relatively inexpensively and by teams of volunteers, by desk-audit. Other aspects would need laboratory examination and experimentation, and particular care in the design, execution and documentation of the process. These categories of evaluations would therefore be best performed by advocacy organisations that have or can acquire appropriate infrastructure and expertise, or by using subcontractors with appropriate expertise.

An assessment program for IoT devices and systems depends on the establishment and maintenance of yardsticks against which they can be measured. It is desirable for yardsticks to be expressed as formalised standards; but this is seldom feasible with new technologies. During the early phases of a new technology, flexibility is necessary, to provide scope for the technology to be experimented with and mature, but without unduly exposing consumers to risks. It is therefore generally necessary to express yardsticks in the form of principles and functional requirements rather than specifications.

A variety of organisations have drafted principles and functional requirements statements. It is natural that documents that are prepared by corporations that develop technology, by industry associations that represent their interests, and by government agencies that are primarily concerned with economics, all tend to be sympathetic to the development of the technology and to overlook or short-change consumers' interests. On the other hand, documents that are prepared by consumer advocacy organisations are based on less deep technical understanding of the technology, and may have difficulty keeping up with the rapid changes that are common during the early life of a new technology.

Consumer advocacy organisations can address these challenges by analysing sets of guidelines, principles, requirements and specifications from a wide variety of sources, and consolidating them into a single authoritative document. Such a document of course needs to focus on functional requirements rather than implementation details, and to be structured in a way that aids understanding, to avoid duplication, and to reconcile differences in approach among the individuals and organisations that prepared the source-documents.

A further mechanism is suggested that could add to the impetus for change that consumer advocacy organisations can generate.

Industry Standards play an important role in achieving safety and inter-operability. Historically, 'engineering standards' of these kinds have been little-influenced by consumers, because the content is technical in nature, the value-add that consumer advocates could bring is not substantial, funding support for participation by consumer advocates is limited, and priorities commonly lie elsewhere. Generally speaking, despite the limited involvement of advocates for their interests, consumers have been beneficiaries of these mechanisms.

In recent decades, Industry Standards have moved into new spaces. One such area is 'process standards', such as those for quality assurance and associated certification and the granting of 'seals of approval'. Others in process or under discussion include privacy by design, and trust by design. These are far less specific than engineering standards, and the extent to which they deliver against their nominal purpose, and the extent to which consumers benefit from them, is in far greater doubt than is the case with engineering standards. The longstanding marginalisation of consumer advocacy organisations in industry standards processes has continued in this arena, despite the potential contributions that consumers could make being far greater.

A further area is looming as a serious threat to consumer interests. Corporations and industry associations are increasingly expressing 'standards' for specific business processes that have direct impacts on consumers. The term 'customer service standards' is used by ISO to encompass such ideas as codes of conduct, complaints-handling, dispute resolution and privacy impact assessments.

Even in these areas, however, consumer advocacy organisations remain marginalised. In some jurisdictional contexts (e.g. UK, EC), funding is provided to consumer organisations to enable participation; but in the majority of countries no such arrangements exist. In any case, doubts persist about to the extent to which the input from consumer advocates is accorded equivalent status to input from other participants. Consumer perspectives are commonly reflected to only a limited extent in drafts, revisions and published Standards.

Yet these are matters on which consumer advocacy organisations can make considerable and important contributions. Moreover, it is vital that they do so, because otherwise the standards promulgated by industry will represent justification for corporate behaviours that are harmful to consumers. Worse, corporations will be in a strong position to resist adaptation, because they can claim to be 'standards-compliant'. And parliaments, policy agencies, regulatory agencies, ombuds-offices, tribunals and courts would be all-too-likely to accept those claims.

In order to redress this balance, consumer advocacy organisations can make representations about the need for a voice in the process. This is likely to be granted, but only as lip-service. The culture of industry standards organisations remains resistant to actually reflecting the arguments and requirements submitted by and on behalf of consumers. This culture is deep-rooted - and is arguably justifiable in the case of engineering standards. It appears likely to change at best very slowly, and certainly far too slowly to enable influence on IoT.

An alternative approach is for the consumer movement to itself issue Consumer Standards, and submit them into policy processes with the same level of authority as corporations invoke when they flourish Industry Standards.

It is not proposed that Consumer Standards be issued on engineering topics, nor even on broad industry processes such as quality assurance. The area in which consumer advocacy organisations can speak authoritatively is consumer requirements. Requirements encompass:

For Consumer Standards to be achieved, the following are necessary:

In order to be applied to the very urgent need in the the IoT field, the CISO institution would need to be established very quickly, and a small suite of procedural documents would need to be approved very soon afterwards. Performing both of these activities quickly should be feasible. The frame provided by CI lends itself to the CISO institution, and the processes can be developed taking into account prior arrangements within the consumer movement, and some other standards institutions, such as ISO and IETF. (Some elements would of course be actively avoided, but others would be directly relevant).

The first few Consumer Standards issued by CISO would need to be strategically selected, in order to have early impact. It is also vital that they be credible, including that they not be over-stated and not extend beyond consumer advocacy organisations' competencies. Consumer Standards need to sit on the desks of parliamentarians, policy agencies and regulatory agencies, alongside Industry Standards. They need to provide the means whereby inadequacies in Industry Standards can be readily seen.

A further application of Consumer Standards is in the evaluation of particular goods and services. Consumer Standards need to focus on requirements expressed in a functional manner, but in sufficiently specific language to guide corporations in their design and operational activities. Their expression needs to be sufficiently grounded that an unsatisfactory device or online service can be shown to fail against the Standard.

Various publications by CI, and by particular consumer advocacy organisations, lend themselves as a basis for rapid development of specific Proposals for Consumer Standards in particular topic-areas. However, it is envisaged that the level of detail would be rather greater than, for example, the 'Minimum Standards for Tackling IoT Security' (CI/Mozilla/ISOC 2018).

I argued in another context that "Progress will have been made when the media routinely reports that a particular government proposal scores only, say, 27/100 on the Civil Society Human Rights Impact Assessment scale, and that a business project fails on, say, 10 of the 24 mandatory features of the NGOs' Business Project Assessment Standard" (Clarke 2010c). CISO Consumer Standards need to be recognised as the requirements benchmark against which both ISO engineering standards and specific consumer products and services are measured.

Activity has of course occurred in a number of relevant contexts. In particular, ANEC is an international non-profit association that advocates for the interests of consumers in European standardisation, through the three European Standardisation Organisations (ESOs) CEN - (Comite Europeen de Normalisation - www.cen.eu), CENELEC (Comite Europeen de Normalisation Electrotechnique - www.cenelec.eu) and ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute - www.etsi.org). ANEC is financed by the European Union (95%) and EFTA (5%) as an Annex III Organisation.

The purpose of this Working Paper is to establish a framework within which consumer advocacy organisations can identify and evaluate possible initiatives to address consumer interests in IoT. It distinguishes segments of the IoT or eObject space, each of which gives rise to different threats to consumers and hence requires specific treatment. It identifies and outlines threats within four categories, involving consumers' commercial interests, security, the physical self and personal data. After considering the various forms that regulation can take, it identifies both conventional approaches to achieving change and three specific, linked initiatives that may be necessary in order to achieve consumers' objectives.

Extract from Clarke (2008)

Information

Terms of Contract

Security

Choice

Consent

Recourse

Redress

Extract from Clarke (2015), Table 1

Extract from Clarke (2019b), Table 1

1. Analyse

/

Perform Risk Assessment 1.1 Define the Objectives and Constraints 1.2 Identify the relevant Stakeholders, Assets, Values and categories of Harm 1.3 Analyse Threats and Vulnerabilities 1.4 Identify existing Safeguards 1.5 Identify and Prioritise the Residual Risks |

2. Design

/

Prepare for Risk Management 2.1 Identify alternative Safeguards 2.2 Evaluate the alternatives against the Objectives and Constraints 2.3 Select a Design or adapt alternatives to achieve an acceptable Design |

3. Do

/

Perform Risk Management 3.1 Plan the implementation 3.2 Implement 3.3 Review the implementation |

Extract from Clarke (2019b), Table 2

Braithwaite B. & Drahos P. (2000) `Global Business Regulation' Cambridge University Press, 2000

Cal (2018) SB-327 Information privacy: connected devices, at https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB327

CC (2012) 'Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation - Part 1: Introduction and general model' Common Criteria, CCMB-2012-09-001, Version 3.1, Revision 4, September 2012, at http://www.commoncriteriaportal.org/files/ccfiles/CCPART1V3.1R4.pdf

Chen Y. & Cheung A. (2017) 'The Transparent Self Under Big Data Profiling: Privacy and Chinese Legislation on the Social Credit System' University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2017/011 , at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2992537

CI (2017) 'Securing consumer trust in the internet of things: Principles and Recommendations' 2017, at https://www.consumersinternational.org/media/154809/iot-principles_v2.pdf

CI (2019) 'Checklist for retailers of connected products and services marketed to children or for children' Consumers International, March 2019, at https://www.consumersinternational.org/media/214943/iot-retailer-checklist-eng.pdf

CI/ISOC (2019) ' The trust opportunity: Exploring Consumers' Attitudes to the Internet of Things' Consumers International / ISOC, May 2019, at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CI_IS_Joint_Report-EN.pdf

CI/Mozilla/ISOC (2018) 'Minimum Standards for Tackling IoT Security'

Consumers International, Mozilla and ISOC, November 2018, at

https://medium.com/read-write-participate/minimum-standards-for-tackling-iot-security-70f90b37f2d5

Cisco (2016) 'Securing the Internet of Things: A Proposed Framework' Cisco, December 2016, at https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/about/security-center/secure-iot-proposed-framework.html

Clarke R. (2001) 'Meta-Brands' Privacy Law & Policy Reporter 7, 11 (May 2001), PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/MetaBrands.html

Clarke R. (2006) 'A Major Impediment to B2C Success is ... the Concept 'B2C'' Invited Keynote, Proc. ICEC'06, Fredericton NB, Canada, 14-16 August 2006, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/ICEC06.html

Clarke R. (2008) 'B2C Distrust Factors in the Prosumer Era' Invited Keynote, Proc. CollECTeR Iberoamerica, Madrid, June 2008, pp. 1-12, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/Collecter08.html

Clarke R. (2010a) 'User Requirements for Cloud Computing Architecture' Proc. 2nd International Symposium on Cloud Computing, Melbourne, May 2010. Published in Parashar M. & Buyya R. (2010) Proc. 10th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing, Melbourne, Australia, 17-20 May 2010, pp. 625-630, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/CCSA.html

Clarke R. (2010b) ' The Cloudy Future of Consumer Computing' Proc. Bled eConference, June 2010, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/CCC.html

Clarke R. (2010c) 'Civil Society Must Publish Standards Documents' Proc. Human Choice & Computers (HCC9), IFIP World Congress, Brisbane, September 2010, pp. 180-184, at http://www.springerlink.com/content/q3nwp17134634g45/, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/CSSD.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'Approaches to Impact Assessment' Notes for a Panel Presentation at CPDP'14, Brussels, 22 January 2014, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/IA-1401.html

Clarke R. (2015) 'The Prospects of Easier Security for SMEs and Consumers' Computer Law & Security Review 31, 4 (August 2015) 538-552, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/SSACS.html

Clarke R. (2019a) 'Risks Inherent in the Digital Surveillance Economy: A Research Agenda' Journal of Information Technology 34,1 (Mar 2019) 59-80, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/DSE.html

Clarke R. (2019b) 'Principles and Business Processes for Responsible AI' Computer Law & Security Review 35, 4 (Jul-Aug 2019), PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/AIP.html

Clarke R. (2019c) 'Regulatory Alternatives for AI' Computer Law & Security Review 35, 4 (Jul-Aug 2019), PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/AIR.html

Clarke R. & Wigan M.R. (2018) 'The Information Infrastructures of 1985 and of 2018: The Sociotechnical Context of Computer Law & Security' Computer Law & Security Review 34, 4 (Jul-Aug 2018) 677-700, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/IIC18.html

DoCA (2018) 'Impacts of 5G on productivity and economic growth' Department of Communications and the Arts, April 2018, at https://www.communications.gov.au/file/35551/download?token=0MlSFttv

Drahos P. (ed.) (2017) 'Regulatory Theory: Foundations and Applications' ANU Press, 2017. at http://press.anu.edu.au/publications/regulatory-theory/download

Firesmith D. (2004) 'Specifying Reusable Security Requirements' Journal of Object Technology 3, 1 (Jan-Feb 2004) 61-75, at http://www.jot.fm/issues/issue_2004_01/column6

Gunningham N., Grabosky P, & Sinclair D. (1998) 'Smart Regulation: Designing Environmental Policy' Oxford University Press, 1998

ICIJ (2019) 'Implant Files' International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 2019, at https://www.icij.org/investigations/implant-files/

IETF (2007) 'Internet Security Glossary ' Internet Engineering Task Force, RFC 4949, Version 2, August 2007, at https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4949

IoTA (2018) 'IoT Security & Privacy Trust Framework' IoT Alliance and ISOC, v2.5, May 2018, at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/iot_trust_framework2.5a_EN.pdf

IoTAA (2017) 'Internet of Things Security Guideline' IoT Alliance Australia, v.1.2., November 2017, at http://www.iot.org.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/IoTAA-Security-Guideline-V1.2.pdf

IoTSF (2018) 'IoT Security Compliance Framework' IoT Security Foundation, Release 2, December 2018, at https://www.iotsecurityfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IoTSF-IoT-Security-Compliance-Framework-Release-2.0-December-2018.pdf

ISO (2011) 'Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects -- Good clinical practice' ISO 14155:2011

ISO (2012) 'Information Technology - Security Techniques - Information Security Risk Management' International Standards Organisation, 27005:2012

ISO (2018) 'Information technology -- Security techniques -- Vulnerability disclosure' ISO/IEC 29147:2018, International Organization for Standardization, October 2018

ISOC (2015) 'The Internet of Things: An Overview: Understanding the Issues and Challenges of a More Connected World' The Internet Society, October 2015, at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/df53/501af80026c4379a3467b551caaf7589a1db.pdf?_ga=2.100900997.502167948.1562555425-204017813.1562555425

ISOC (2018) 'IoT Security for Policymakers' Internet Society, April 2018 at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IoT-Security-for-Policymakers_20180419-EN.pdf

ISOC (2019) 'Canadian Multistakeholder Process: Enhancing IoT Security' The Internet Society, May 2019, at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Enhancing-IoT-Security-Report-2019_EN.pdf

Lessig L. (1999) 'Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace' Basic Books, 1999

Liang F., Das V., Kostyuk N. & Hussain M.M. (2018) 'Constructing a Data_Driven Society: China's Social Credit System as a State Surveillance Infrastructure' Policy and Internet 10, 4 (December 2018)

McFadden M., Wood S., Mangtani R. & Forsyth G. (2019) 'The economics of the security of consumer-grade IoT' Plum Consulting and the Internet Society, April 2019, at https://www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2019/the-economics-of-the-security-of-consumer-grade-iot-products-and-services/

Madaan N., Ahad M.A. & Sastry S.M. (2018) 'Data integration in IoT ecosystem: Information linkage as a privacy threat' Computer Law & Security Review 34 (2018) 125-133

Manwaring K. (2017) `Emerging Information Technologies: Challenges for Consumers' Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 17, 2 (August) 265-289

Manwaring K. (2018) 'Will emerging information technologies outpace consumer protection law? -- The case of digital consumer manipulation' Competition & Consumer Law Journal 26, 2 (2018) 141-181

Manwaring K. & Clarke R. (2015) 'Surfing the third wave of computing: a framework for research into eObjects' Computer Law & Security Review 31,5 (October 2015) 586-603, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/SSRN-id2613198.pdf

NIST (2019) 'Considerations for a Core IoT Cybersecurity Capabilities Baseline' US National Institute of Standards and Technology, February 2019, at https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2019/02/01/final_core_iot_cybersecurity_capabilities_baseline_considerations.pdf

OTA (2017) 'IoT Security & Privacy Trust Framework v2.5' Online Trust Alliance, 14 Oct 2017, at https://otalliance.org/system/files/files/initiative/documents/iot_trust_framework6-22.pdf

Svantesson D.J.B. & Clarke R. (2010) 'A best practice model for e-consumer protection' Computer Law & Security Review 26, 1 (Jan-Feb 2010) 31-37, PrePrint at http://epublications.bond.edu.au/law_pubs/346

UK (2018) 'Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security' UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, October 2018, at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/773867/Code_of_Practice_for_Consumer_IoT_Security_October_2018.pdf

UNGCP (2016) 'United Nations Guidelines for Consumer Protection' United Nations Conference On Trade And Development, 2016, at https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditccplpmisc2016d1_en.pdf

Xavier C., Bosua R., Maynard S.B. & Ahmad A. (2016) 'The Internet of Things (IoT) and its impact on individual privacy: An Australian perspective' Computer Law & Security Review 32 (2016) 4-15

Zuboff S. (2019) 'The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power' Public Affairs Books, 2019

TEXT

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor in Cyberspace Law & Policy at the University of N.S.W., and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University. He is a longstanding Board-member and past Chair of the Australian Privacy Foundation. He is also a longstanding Director and Company Secretary of the Internet Society of Australia, and participated in the Estoril Summit in that role, under a travel grant proivided by the Internet Society.

Dan J B Svantesson and Roger Clarke. (2010) 'A best practice model for e-consumer protection' Computer Law & Security Review 26, 1 (Jan-Feb 2010) 31-37, at http://epublications.bond.edu.au/law_pubs/346

Exctract from CI/Mozilla/ISOC (2018)

The product must use encryption for all of its network communications functions and capabilities. This ensures that all communications are not eavesdropped or modified in transit.

The product must support automatic updates for a reasonable period after sale, and be enabled by default. This ensures that when a vulnerability is known, the vendor can make security updates available for consumers, which are verified (using some form of cryptography) and then installed seamlessly. Updates must not make the product unavailable for an extended period.

If the product uses passwords for remote authentication, it must require that strong passwords are used, including having password strength requirements. Any non unique default passwords must also be reset as part of the device's initial setup. This helps protect the device from vulnerability to guessable password attacks, which could result in device compromise.

The vendor must have a system in place to manage vulnerabilities in the product. This must also include a point of contact for reporting vulnerabilities or an equivalent bug bounty program. This ensures that vendors are actively managing vulnerabilities throughout the product's lifecycle.

The product must have a privacy policy that is easily accessible, written in language that is easily understood and appropriate for the person using the device or service. Users should at minimum be notified about substantive changes to the policy. If data is being collected, transmitted or shared for marketing purposes, that should be clear to users and, as in line with GDPR, there should be a way to opt-out of such practices. Users should also have a way to delete their data and account. Also in line with the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this should include a policy setting standard retention periods wherever possible.

OTA (2017) 'IoT Security & Privacy Trust Framework v2.5', Online Trust Alliance, 14 Oct 2017, at https://otalliance.org/system/files/files/initiative/documents/iot_trust_framework6-22.pdf

Applicable to any device or sensor and all applications and back-end cloud services. These range from the application of a rigorous software development security process to adhering to data security principles for data stored and transmitted by the device, to supply chain management, penetration testing and vulnerability reporting programs. Further principles outline the requirement for life-cycle security patching.

Requirement of encryption of all passwords and user names, shipment of devices with unique passwords, implementation of generally accepted password reset processes and integration of mechanisms to help prevent "brute force" login attempts.

Requirements consistent with generally accepted privacy principles, including prominent disclosures on packaging, point of sale and/or posted online, capability for users to have the ability to reset devices to factory settings, and compliance with applicable regulatory requirements including the EU GDPR and children's privacy regulations. Also addresses disclosures on the impact to product features or functionality if connectivity is disabled.

Key to maintaining device security is having mechanisms and processes to promptly notify a user of threats and action(s) required. Principles include requiring email authentication for security notifications and that messages must be communicated clearly for users of all reading levels. In addition, tamper-proof packaging and accessibility requirements are highlighted.

ISOC (2018) 'IoT Security for Policymakers' Internet Society, April 2018 at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IoT-Security-for-Policymakers_20180419-EN.pdf

Strengthen accountability for IoT security and privacy by providing well-defined responsibilities and consequences for inadequate protection.

Increase incentives to invest in security by fostering a market for trusted independent assessment of IoT security.

Encourage security as a component of all stages of the product lifecycle, including design, production and deployment. Strengthen the ability of stakeholders to respond and mitigate IoT-based threats.

Governments can use their policy tools, significant resources, and market power to make security a competitive differentiator.

Security solutions should not be based on specific technical standards or vendor products, but instead based on desired outcomes such as better security, privacy, and interoperability. These goals will not likely change frequently, but the means to achieve them will.

As security is expensive and users may have difficulty recognizing or valuing security, policy and law can have an important role to play in shaping security practices in the IoT industry. Policies can be developed with a goal of influencing the IoT ecosystem to promote better security practices, rather than to mandate specific technical solutions.

NIST (2019) 'Considerations for a Core IoT Cybersecurity Capabilities Baseline' US National Institute of Standards and Technology, February 2019, at https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2019/02/01/final_core_iot_cybersecurity_capabilities_baseline_considerations.pdf

UK (2018) 'Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security' UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, October 2018, at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/773867/Code_of_Practice_for_Consumer_IoT_Security_October_2018.pdf

Diagram extracted from ISOC (2019) 'Canadian Multistakeholder Process: Enhancing IoT Security' The Internet Society, May 2019, at https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Enhancing-IoT-Security-Report-2019_EN.pdf, p.70

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 28 April 2019 - Last Amended: 15 July 2019 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/II/IoTCP.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy