Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Emergent Draft of 16 June 2021

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2021

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IDM-POE.html

This is the 2nd article in a series that presents and articulates a model of entities and identities that supports the design of effective information systems. Each is designed to be read as a standalone article, but are likely to be more fully appreciated if read in sequence. The series overview is at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IDM-O.html.

The field of 'identity management' has been fraught for decades, with the battlefield strewn with the corpses of hundreds of failed schemes, and the techniques in use scarred by innumerable deficiencies. The work reported here reflects the author's longstanding belief that the problems derive from a longstanding mis-fit between designers' conceptions of the need, on the one hand, and the complexities of the real world on the other.

The author's previous endeavours during the period 1990-2010 presented an explicit model of real-world entities and identities that had considerable similarities with the implicit models used in industry and government, but also some important differences. A weakness of that model, however, was that it was not sufficiently grounded in existing theory, and hence was too easily dismissed by critics as being ad hoc. This paper re-visits the problem-area, this time building on prior work in philosophy and the information systems (IS) literature. The establishment of intellectual foundations has given rise to some adjustments to the presentation of the model and the terminology used in describing it.

Among the wide variety of possible philosophical assumptions, an approach is selected that reflects the pragmatic world of IS practice. This is directly relevant to that portion of IS research that seeks to deliver information relevant to IS practice. Given the recent, very strong tendency within the IS discipline towards sophistication and intellectualisation, and preference for addressing other researchers to the effective exclusion of IS professionals, the pragmatic metatheoretic model presented here will not be relevant to all research.

The purpose of the model is to reflect the relevant complexities, and hence to guide organisations in devising architectures and business processes for IS that reflect real-world things and events, with a particular focus on systems in which some of the real-world things are human beings. This extends to such applications as user registration, sign-on and identity management. Inanimate entities are addressed first, enabling a relatively mechanistic approach to be adopted. Expanding the scope of entities to human beings involves much more careful attention to interests, rights and values, necessitating some further layers of complexity in the model.

[ REVISIT THIS LATER: ]

IS is concerned with system that handle data in a variety of ways. Distinctions are made between data processing (DP) systems, information systems (IS), decision support systems (DSS), and systems that act directly on the Real-World based on data handled in the Abstract-World on the basis on the models underlying Abstract-World systems.

Further important concepts are then discussed that underpin the models that enable IS to function. Real-world phenomena involve Entities that fall into different categories (such as the class of objects commonly called shipping containers) and Entity-Instances (in this case, particular shipping containers). Individual Entity-Instances are distinguished by particular Data-Items, which are usefully referred to as Entifiers.

An Entity-Instance is distinguished from other Entity-Instances by Entifiers such as the registration-number painted on the container. (If no Entifier exists, the Entity is a undifferentiated bulk commodity, such as a category of oil, a quality-level of coal, wheat or barley). Entification involves association of Data with an Entity-Instance.

An Entity may adopt various Identities. For example a particular Entity-Instance of a shipping container may be associated with a slot on a ship (or a truck or container flat-wagon for railway-haulage), or in a container-depot, or the cargo that it currently contains, or the lock currently on the door, or the refrigeration-unit installed in it. The process of Identification involves the association of Data with an Identity-Instance.

All of these concepts are applicable to (Id)Entities of all kinds, including inanimate objects, and living objects such as animals, including people. Their use in relation to inanimate objects and even animals is subject to few constraints. Mechanistic application to human beings is, on the other hand, fraught with difficulties, because human rights intrude. In the context of Data about humans, a number of further concepts are therefore relevant.

Of particular significance is Nymity, which arises where a particular Identity cannot be reliably associated with a particular Entity (Anonymity), or association can only be achieved if particular conditions are satisifed (Pseudonymity). The concept of a Nym encompasses both Pseudonyms and Anonyms.

The term Digital Persona refers to a Data Record that is sufficiently rich to provide someone with access to the record with an impression of the represented Entity or Identity that can be used in the Abstract-World as a proxy for the Real-World (Id)Entity.

Authentication is a process that establishes a level of confidence in an Assertion.

Assertions are of many kinds, including Value Assertions (this string of binary digits represents a bitcoin, millibitcoin or a satoshi), and Factual Assertions (an event occurred, such as a solar flare or a vehicle passing under a tollway gantry).

Of particular significance are Attribute Assertions (data-item represents the state of a particular Property of a particular (Id)Entity-Instance at a particular time, e.g. loadedness or otherwise of a container, or operational-readiness of the refrigeration-unit currently installed in it). A special case relevant to people and organisations is a Principal-and-Agent assertion (that a particular (Id)Entity-Instance has the legal authority to act on behalf of another (Id)Entity-Instance).

Another assertion-type of importance is that a particular Real-World (Id)Entity-Instance is appropriately associated with a particular (Id)Entifier, such as a container-number, or a Bill of Lading of an item of cargo stored inside it.

The model and the concepts it embodies are capable of being applied in a wide range of concepts. It is contended that, although some further model complexity is needed in some circumstances, this is a minimally sufficient model in many circumstances, variously to evaluate the design of particular, existing information systems, or to design new ones.

One application area of particular significance is to the notions of Data Quality and Information Quality. Another is the evaluation of so-called 'identity management' schemes used by organisations, both in physical/'meatspace' contexts and in electronic/digital/virtual/'cyberspace' contexts. Particular virtual domains in which (Id)Entity Authentication is often applied, but faces considerable challenges, include eCommerce, eBusiness and eGovernment systems.

[ SET THE CONTEXT: ]

longstanding and ongoing difficulties in the area of identification and authentication, particularly where the entities in question are human beings

contention that suitable designs depend on a much better appreciation by designers of the nature of the phenomena they seek to document and to exercise control over

that in turn depends on a model that is pragmatic, in the sense of fitting to the needs of IS practitioners, but that also reflects insights from relevant aspects of philosophy

[ DECLARE THE PURPOSE: ]

to draw on ontology, epistemology and axiology in order to establish an outline metatheoretic model

to further articulate that model, in order to provide a robust framework for identification and authentication in IS

Wherever possible, the model presented here uses conventional terms in conventional ways. For each such term, it provides a definition that relates it to the remainder of the framework. Once defined, all of the key terms are thereafter referred to using an initial capital. However, many common usages of terms are ambiguous, inconsistent or unhelpful and even harmful to the effective design and operation of information systems. In these cases, terms are used, and in some cases varied or invented, in ways that are materially different from common usage. All are defined in ways that inter-relate them with other relevant terms within the model.

[ REVISE THE STRUCTURE ONCE IT STABILISES: ]

The paper commences with an outline of the philosophical underpinnings of the analysis, including a model that introduces the key concepts. This comprises metatheoretic assumptions in three areas, relating to existence (ontology), knowledge (epistemology) and value (axiology). {A review of the scope of the IS field is presented. (Why?) ] The initial model is then further articulated. The examples are initially concerned with inanimate real-world things. A further section then considers the additional factors involved when the real-world things are human beings. The notion of authentication is then mapped against the model, enabling its full richness to be appreciated. Several applications of the complete model are identified.

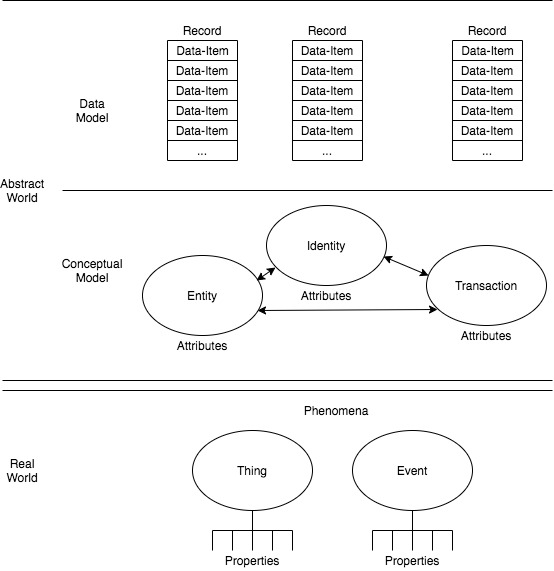

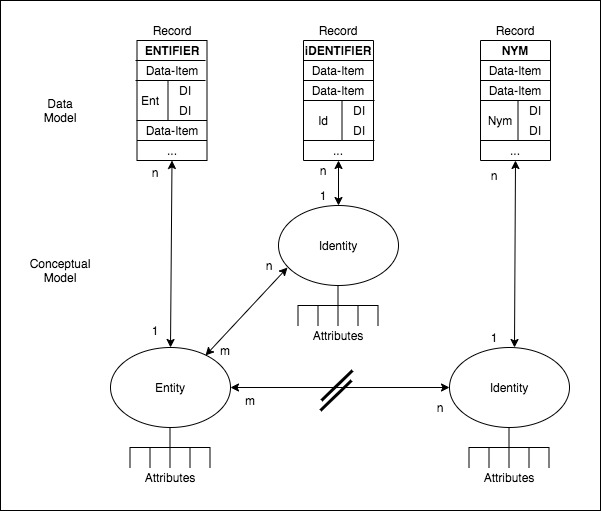

This section establishes the philosophical foundations underlying the model put forward in the later sections of the paper. First, the approach developed in Clarke (2021) is briefly re-presented and extended. The section begins by identifying the elements of a conventional ontological position, involving the nature of reality and the relationship between humans and reality. It then declares assumptions of an epistemological nature, regarding what it means when we say that humans know things about the world. The third sub-section explains the axiological position, relating to the ways in which humans make value-judgements about alternative outcomes and hence about alternative strategic decisions. Figure 1 supports the textual explanations with a visual depiction of the key elements of the model.

The pragmatic approach adopted is that there is a reality, outside the human mind, where things exist (a position commonly referred to as 'realism'). Humans cannot directly know or capture those things. They can, however, sense and measure those things and create data reflecting them, and construct an internalised model of those things (an assumption closely related to the ontological assumption called 'idealism').

The model in Figure 1 accordingly distinguishes a Real World from an Abstract World. The Real World comprises Things and Events, collectively Phenomena, which have Properties. These can be sensed by humans and artefacts with reliability varying across a very wide spectrum. Humans create an Abstract World in which Entities are postulated that are intended to correspond to Real-World Things, and Attributes of Entities to represent the Properties of Things. Events give rise to changes in the Properties of Things, and these are reflected in the Abstract-World as Transactions that give rise to changes in Entitities' Attribute-values.

The abstract concept of an Identity, developed further below, caters for the different ways in which Entities present in different circumstances. The various kinds of Entities and Identities have Relationships with one another, represented by arrows in the depiction in Figure 1. The Relationships also have Attributes. Further discussion of these aspects of the model is provided in the following sub-sections.

In the IS field, it is necessary to adopt a flexible conception of what constitutes the Real-World. This is because some of the IS that practitioners develop, maintain and operate represent imaginary Things. Some IS model possible future IS, to, for example, assess those imagined or intended IS's operational efficiency or security. Other IS model purely formal systems such as games-worlds. Another category of pseudo-Real-Worlds involves past, possible future, and even entirely hypothetical contexts, such as the Earth's atmosphere millions of years ago, or following a large-scale meteorite strike, or 50 years from now, with and without stringent measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge. The pragmatic assumptions adopted here are that both of the two alternative categories of philosophical theories are applicable, but in different circumstances. The proposition of 'empiricism' is that knowledge is derived from sensory experience. This works well in circumstances where the Things represented by Entities are inanimate, their handling is largely mechanical, and codified knowledge exists and is readily transmissible. This can apply, for example, in the cases of aircraft guidance systems and robotic production-lines.

On the other hand, some kinds of knowledge are internal and personal. The 'apriorist' or 'rationalist' proposition is that 'tacit knowledge' exists only in the mind of a particular person, is informal and intangible, and hence is not readily communicated to others. A different form of knowledge, usefully referred to as codified knowledge, can only emerge where individuals' insights can be extracted and structured. Comprehensive propositional ('know that') knowledge may be hard to come by, variously because of unstable phenomena, a high degree of environmental variability, or craft activities with a strong skills-base and hence a predominance of procedural ('know how to') knowledge. A pragmatic approach must support modelling not only in contexts that are simple, stable and uncontroversial, but also where there is no expressible, singular, uncontested 'truth'.

The Abstract World is depicted in Figure 1 at two levels. The Conceptual Model level endeavours to reflect the modeller's perception of the Things, the Events and their Properties, by postulating Entities and Entity-Instances, presentations of Entities called Identities, and Transactions, with Relationships of various kinds among them, all with Attributes. The notion of an Entity corresponds to a category of Things, and Transaction to a category of Events. The ideas and terms used in this paper, and articulated further below, are similar to, but not identical with, related ideas in the well-developed and diverse sub-discipline of conceptual modelling.

In the dialect used by ontologists, the term 'universal' corresponds to a category, and 'particular' refers to an instance. For example, in biology, the notion 'species' (e.g. African Elephant) is a universal, and the notion 'specimen' is a particular. An example that is perhaps more pertinent to IS is the cargo-containers, which is a universal or Entity, whereas a specific cargo-container is a particular or Entity-Instance.

The other level, referred to here as the Data Model, enables the operationalisation of the relatively abstract ideas in the Conceptual Model level. The notions of record, data-item, and data-item-value are discussed in this sub-section. The means whereby particular data-items, alone or in groups, may be used to differentiate among instances, by means of Entifiers and Identifiers, is addressed in a later section of this paper. Beyond data, the epistemological aspects of the pragmatic model comprise assumptions made about information, knowledge and wisdom.

The singular term 'datum' has fallen into disuse in recent times. The term 'data', used variously as a plural and as a generic noun, refers to any quantity, sign, character or symbol, or collection of them, that is in a form accessible to a person or a machine. 'Real-world data' or 'empirical data' is data that represents or purports to represent some Property of a Real-World Phenomenon. That can be contrasted with 'synthetic data', which is data that bear no direct relationship to any real-world phenomenon, such as the output from a random-number generator, or data created as a means of testing the performance of software under varying conditions.

The vast majority of real-world Things and Events do not give rise to data. The background noise emanating from all points of the universe has been ignored for millions of years, until the last few decades, during which some astronomers have occasionally sampled a tiny amount of it. Some things about the trucks that carry goods in and out of a company's gates are of great interest to someone (such as which trucks, when, what they carried in, and what they carried out). But there is seldom any motivation to measure, let alone record, the pressure in the tyres on the trucks, the number of chip-marks in the paintwork, the condition of the engine-valves, or even the number of consecutive hours the driver has been at the wheel.

Of the real-world Things and Events for which data is sensed or created, many kinds are very uninteresting. The streams of background noise emanating from various parts of the sky might on occasions contain a signal from a projectile launched from the earth, and just possibly might contain some pattern from which an inter-stellar event can be inferred, or perhaps the existence of intelligent life somewhere in the universe. But usually the contents are devoid of any value to anyone. Similarly, a great deal of the data stored by commerce, industry and government is of interest for only a very short time, or 'just for the record', and kept only for contingencies, or because it was easier or cheaper than deleting it.

The term 'information' is used in many ways. Frequently, even in refereed sources, it is used without clarity as to its meaning, and often in a manner interchangeable with Data. The pragmatic model adopted in this paper uses the term 'Information' for a sub-set of data: that data that has value. Data has value in only very specific circumstances. Until it is in an appropriate context, Data is not Information, and once it ceases to be in such a context Data ceases to be Information.

The most straightforward way in which Data is useful is when it is relevant to a decision. A person's interest in the weather depends on whether that person has an interest in the conditions outside, and on where the person is now, or is going to. Data about a delivery of a particular batch of baby-food to a particular supermarket is lost in the bowels of the company's database, never to come to light again, unless and until something exceptional happens, such as the bill not being paid, the customer complaining about short delivery, or an extortionist claiming that poison has been added to some of the bottles.

The question as to what data is 'relevant to a decision' is not always clear-cut. On a narrow interpretation, Data is relevant and of value only if it actually makes a difference to the decision made. A broader interpretation is that Data is relevant and therefore of value if, depending on whether or not it is available to the decision-maker, it could make a difference to the decision.

In addition to decision-making, there are other circumstances in which Data can be interesting or valuable. When we read the newspaper, listen to the news on the radio, or watch 'infotainment' programs on television, we are seldom making decisions, and yet we perceive informational value in some of the Data presented to us. Sometimes it is merely humorous. Sometimes it is not what we would have expected, and therefore has 'surprisal' value ("Gosh! The government might survive the election yet!" Or "An injury incurred in training will keep the star fullback out of the Grand Final!"). In other cases, it may be something that fits into a pattern of thought we have been quietly and perhaps only semi-consciously developing for some time, and which seems, for no very clear reason, to be worth filing away. Some people feel very uncomfortable with this definition. Its looseness, fuzziness and instability are confronting. Rather than a nice, straightforward 'thing', describable in mathematical terms, and analysable using formidable scientific tools, this definition makes Information rubbery and intangible, a 'will o' the wisp'.

The question then arises as to how Data and Information relate to knowledge. Two contrasting conceptions of knowledge exist. One asserts that knowledge is a body of facts and principles accumulated by humankind over the course of time, that are capable of being stored in a warehouse. The other argues that facts and principles cannot be meaningful outside the mind of a human. Within the second school of thought, knowledge is the matrix of impressions within which an individual situates newly acquired information.

In order to bridge these two extremes, the pragmatic approach adopted in the model being presented here is that the term 'Knowledge' is to be avoided, except when qualified by one of two adjectives:

The assumption is often made that wisdom is closely related to Data, Information and Knowledge. Some presenters go so far as to depict a simple pyramidal arrangement, with large volumes of Data forming the base layer, smaller volumes of Information at the second-lowest layer, a slimmer, second-highest layer called Knowledge, and a layer at the peak called wisdom. The pragmatic model used here rejects such ideas as simple-minded and dangerous. It treats wisdom as being on an entirely different plane from Information, from Codified Knowledge and even from Tacit Knowledge.

The model assumes that, to the extent that 'Wisdom' exists, it is one of the following:

The final element of the pragmatic metatheoretic model is concerned with value. The values dominant in many organisations are operational, financial and economic. However, many contexts arise in which there is a pressing need to recognise broader economic interests, and values on the individual, social and environmental dimensions. Human values are particularly prominent in systems in which people are key players or users, and in systems that materially affect uninvolved people, usefully referred to as 'usees'.

The pragmatic approach to value recognises that:

[[ IS ANY OF THIS SECTION RELEVANT TO THIS SERIES OF PAPERS?

[[ IN PARTICULAR, IS THIS RELEVANT SOMEWHERE?

The working definition of the scope of Information Systems (IS) research adopted in this work is that it is the multi-disciplinary study of:

The practice of IS involves the design of systems to handle data and provide information to people, utilising information technologies (IT) as tools in the achievement of organisational and personal objectives.

]]

In IS practice, and practice-relevant IS research, the focus is less on Real-World systems that exchange energy, and more on Real-World systems in which Events occur that are usefully reflected in Abstract-World transactions giving rise to changes in Real-World Things.

Several categories of IS are distinguished. They emerged in the sequence presented below, reflecting the increases in capacity and sophistication in IS and IT across the last four decades of the 20th century.

A Transaction Data Processing (DP) System 'captures' Data, in some sense of that word, manipulates it in ways useful to some purpose, and stores it in an manner organised in such a way that it can be discovered and accessed when needed. The notion of 'data capture' encompasses a number of diferent techniques, including:

In IS practice, an Information System (IS), used in a specific rather than a generic sense, is a set of interacting activities by humans and artefacts that performs one or more functions involving the handling of Data, including Data collection, creation and editing; Data processing and storage; generation of Information through selection, filtering, aggregration, presentation and use; Data disclosure; and Data retention, archival and destruction.

From a research viewpoint, the domain of IS is the study of information production, flows and use. The emphasis has been strongly on the use of Data and Information within organisations. In the US Business School tradition, the scope is narrow in that the beneficiary of the IS is predominantly, and even exclusively, an organisation, and the term Management Information System (MIS) is applied.

The scope of IS began with intra-organisational systems. As technologies matured and computing devices came to be used by individual people, and as the marriage of computing with communications enabled the interconnection of artefacts over distance, it progressively became feasible to operate inter-organisational systems (one-to-one), and then multi-organisational systems in various configurations. This culminated in open networks, with many systems now operating extra-organisationally, that is to say reaching beyond organisational boundaries to individuals.

There has also come to be a strong emphasis on the use of technology, often leading to narrow perspectives, miconceptions, unnecessary errors and harm, and missed opportunities. This evidences its most extreme and limiting form where the focus of the discipline is narrowed down to 'the IT artefact', and all other considerations are warped by that limitation.

A Decision Support System (DSS) uses available Empirical Data from operational support systems, combined with hypothetical or Synthetic Data, to enable 'what-if' investigations, and hence support strategic rather than tactical activities. Strategic thinking re-emphasises the importance of clarity about models of the relevant current and possible future realities.

A further category for which no mature term yet exists is IS that act in the Real-World. These take advantage of the marriage of computing and communications with robotics, by including actuators that enable direct action by elements of the system on the Real-World. The significance of this category of system is that actions may be delegated to artefacts, and arise from automated decisions. Those decisions may be based on fixed computational approaches ('algorithms' in the proper sense of the term), or on rule-based computations which are more or less analysable and capable of being subjected to scrutiny, or on opaque and inscrutably adaptive computational approaches applied to a sample of Empirical Data (commonly referred to as machine learning - ML, typically applying artificial neural network techniques - ANN). This has the effect of denying human review prior to action being taken.

IS that embody automated decisions and actions challenge the epistemological assumptions underlying IS practice and research, in that some aspects of Information and Codified Knowledge may require reconsideration in the context of automated decision-making, particularly where it is of an inscrutable nature. Meanwhile, axiological assumptions are severely challenged by the apparent incapacity of such systems to embody human, social and environmental values.

This section articulates the notions of Entity and Identity, which are the two central features of the pragmatic metatheoretic approach adopted in this paper. It draws heavily on a prior working paper (Clarke 2001a) and a previous published article (Clarke 2010a-d), but re-casts the model in light of the metatheoretic discussions above. It first considers them within the Conceptual Model level, and then at the Data Model level. The notions are applied in this section to inanimate Real-World Things. The following section addresses additional considerations that arise when the Things are human beings.

The Entity notion adopted here has a great deal in common with the approach used in a wide range of conceptual modelling techniques; whereas the Identity notion diverges somewhat from the mainstream. An 'Entity' is an element of a Conceptual Model that corresponds with a Real-World Thing. It is a category or collective notion, or a set of instances. In one sense, recognition of Things and entities is arbitrary, because a modeller can postulate whatever they want to postulate. Generally, however, a modeller has a purpose in mind, and postulates a category judged likely to be useful in understanding some part of the Real-World, and contributing to its management.

Examples of an Entity are the set of all cargo-containers, or the mobile-phones assigned by an organisation to its employees. Some objects comprise nested layers of objects. For example, cargo-containers may contain pallet-loads, and within that cartons, and within each carton smaller boxes. Each specific occurrence within the set of objects that makes up an Entity is an 'Entity-Instance'. Hence the Entity cargo-containers comprises many Entity-Instances, one for each particular container, and possibly many nested layers of Entity-Instances.

Each of the many specific conceptual modelling techniques has terms that correspond with those used here. In the case of the original Entity-Relationship Model of Chen (1976), an Entity corresponds with Chen's entity-set ("Entities are classified into different entity sets such as EMPLOYEE, PROJECT, and DEPARTMENT" (p.11)", and Entity-Instance coresponds to Chen's entity: "An entity is a 'thing' which can be distinctly identified. A specific person, company, or event is an example of an entity" (Chen 1976, p.10). An Entity may have 'Entity-Attributes', each of which is an element of a Conceptual Model that corresponds with a Real-World Property. Containers, for example, have a colour, an owner, a type (e.g. refrigerated, or half-height), and various kinds of status (e.g. dirty or clean; and empty or loaded).

Many kinds of Entity are perceived rather differently by the modeller, depending on the context. An 'Identity' is a particular presentation of an Entity, as arises when it performs a particular role. A 'Role' is a pattern of behaviour adopted by an Entity. An Entity may adopt one Identity in respect of each Role, or may use the same Identity when performing multiple Roles.

An 'Identity-Instance' is a particular occurrence of an Identity. For example, any particular motor-vehicle is an Entity-Instance; but a motor-vehicle may at any given time be associated with an Identity-Instance, such as 'the getaway-car', 'the car carrying a person-at-risk' (e.g. the Pope), or 'the lead-vehicle in a convoy'. Another example is a single computing device, which is an Entity-Instance, supporting many processes that interact with one another and with processes running in other devices, each process being an Identity-Instance.

Whereas an Entity necessarily has physical form, an Identity may have virtual form. An example of an Identity with physical form is the set of all SIM-cards inserted into mobile phones. Virtual form, on the other hand, is apparent in the case of processes running in consumer computing devices and communicating with other processes running in that or some other device. An Identity is related to the notion of role in Chen's ER Model: "The role of an entity in a relationship is the function that it performs in the relationship" (p.12).

This usage is very different from that attributed to it during recent decades by organisations that gather data from various sources and use it as a proxy for a human Entity. This has given rise to the problematic business offering referred to as 'identity management'. Better terms exist to describe that notion, such as 'digital persona', which is discussed later in this article. The term 'identity' has widespread usage among normal people to refer to a real-world phenomenon evidenced by human beings, and it is important that observers respect that usage rather than co-opting the term for other purposes.

An Identity may have 'Identity-Attributes', each of which is an element of a Conceptual Model that corresponds with a Real-World Property. Whereas the colour of a car, and its make and model, are Attributes of the Entity, the dangerousness of its occupants is an Attribute associated with the Identity. Similarly, a mobile handset has different attributes from the SIM-card inserted into it, and a computer has different attributes from the various processes running inside it.

A 'Transaction' is an element of a Conceptual Model that corresponds with a Real-World Event. It has Transaction-Attributes that reflect Real-World Properties that the modeller considers to be relevant to the purpose. The function of a 'Transaction-Instance' is to give rise to a change in the state of Attributes for one or more Entity-Instances or Identity-Instances.

A 'Relationship' is a linkage between two elements within the Conceptual Model level. Figure 1 in section 2 above depicts a Relationship between an Entity and an Identity with a line ending in an arrow at each end. This applies for example to mobile-handsets and SIM-cards. Entities may also have Relationships with other Entities, and Identities with other Identities. For example, motor vehicles need to be associated with other motor vehicles under joint contracts for roadside assistance, and where they are involved in the same accident. Similarly, containers need to be associated with the organisations that own them. Organisations also own and insure motor-vehicles, and hence the two Entities organisations and motor-vehicles need to have some form of link between them.

A Relationship may have 'Relationship-Attributes'. Cardinality is a particularly important attribute. At each end of the line depicting a Relationship it may be that no Relationship exists in that direction (cardinality 0), or a single linkage (1) may be mandatory, or a range of linkages may be possible (conventionally, 'n' and 'm', or '0-n' or '1-n). For example, a cargo container must have precisely one linkage with an owner (cardinality 1), whereas the Entity that corresponds to Real-World mobile-phone-handsets may be related to multiple, successive Identity-Instances, associated with different SIM-cards that are inserted into it. The arrow-head on the other end of that line reflects the fact that a SIM-card may be used in multiple, successive mobile-phone-handsets. Similarly, an Entity for motor-vehicles has a one-to-many relationship with an Identity for 'getaway-cars'. Moreover, escapees may use a succession of vehicles, each of which in turn has the Identity 'getaway-car'; so the arrow depicting this Relationship is also two-headed.

In the remainder of this article, when referring to both Entities and Identities, the abbreviation (Id)Entities is applied, and the same approach is adopted to derivative terms such as (Id)Entity-Instance.

The previous sub-section had its focus on the Conceptual Model level. The (Id)Entity notions require further articulation at the Data Model level. The terms Data, Real-World Data, Synthetic Data and Information were introduced in s.2.2 above. The pragmatic approach proposed in this paper embodies several further concepts.

In the abstract world of information systems, each Attribute of an (Id)Entity is represented by a 'Data-Item', which is a storage-location in which a discrete 'Data-Item-Value' can be represented. For example, Entity-Attributes of cargo-containers may be expressed at the Data Model level as Data-Items and Data-Item-Values of Colour = Orange, Owner = MSK (indicating Danish shipping-line Maersk), Type = Half-Height, Freight-Status = Empty.

A collection of Data-Items that refers to a single (Id)Entity-Instance is referred to as a 'Record'. A collection of Records may be referred to as a 'File' or data-set. A Record may relate to a particular Entity-Instance (e.g. a container, or mobile handset) or Identity-Instance (e.g. a SIM-card), or to a Transaction-Instance.

The term 'Metadata' refers to data that describes some attribute of other data. Metadata may be explicitly expressed or captured, by cataloguers; or it may be automatically generated, i.e. inferred by software. It may be stored with the data to which it relates, or stored separately. During the last 2-3 decades, the term has become sufficiently widely-used that hyphenation is no longer common.

The metadata concept is generic, and specific interpretations exist in a wide variety of contexts, including libraries, museums and health care, and for , print-publications and web-pages. Examples relevant to the topic of this paper include the date on which data was collected, the scale against which the data was measured (nominal, ordinal, cardinal or ratio), the meaning imputed to the data at the time of collection, the contexts in which it was collected and has subsequently been stored and transmitted (its 'provenance'), and any supporting evidence for the data's quality.

A vital question that needs to be addressed is the manner in which each individual (Id)Entity-Instance is distinguished from all of the other instances of the same (Id)Entity. Specific terms are adopted in the pragmatic metatheoretic approach proposed in this paper. The term 'Entifier' refers to any one or more Data-Items held in a Record whose value(s), alone or in combination, are sufficient to distinguish any particular Entity-Instance from all other Entity-Instances of the same Entity. The word 'entifier' is not to be found in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), although 'entify' is, with a meaning not unrelated to that used here for 'entifier'. Surprisingly, as far as I can tell, 'entifier' is a neologism, first apparent in Clarke (2001), and first published in Clarke (2003), defined at the time as "the signifier for an entity".

Examples of single-item Entifiers include the BIC-code of a cargo-container (BIC being an abbreviation of Bureau International des Containers), the Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) of a motor-vehicle, and the International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) of a mobile-phone. In some circumstances, a proxy-Entifier may be used, such as the NICId of an installed Ethernet card as a proxy for a computing device.

Artefacts are usually distinguished by Entifiers that are purpose-designed, and hence comprise a single Data-Item. However, an example of a multi-data-item Entifier arises in jurisdictions that re-issue motor-vehicle registration-plates previously allocated to a now-defunct vehicle. To achieve the uniqueness that is highly desirable in an Entifier, a date-range needs to be included as part of the Entifier.

An 'Identifier' is any one or more Data-Items held in a Record whose value(s), alone or in combination, are sufficient to distinguish any particular Identity-Instance from all other Identity-Instances of the same Identity. This is a mainstream use of the term, as evidenced by Oxford English Dictionary (OED) definition 1a: "A thing used to identify someone or something".

Examples of single-item Identifiers include a code assigned by a traffic-control authority to a vehicle of interest, for example when monitoring average speed over a section of road, the Integrated Circuit Card Identification (ICCID) of a SIM-card, and a process-id (e.g. for a software agent).

[ INSERT: Examples of multi-item Identifiers OR hold until the next section ]

Importantly, what constitutes an Identifier is open-ended. The term 'Candidate Identifier' refers to any combination of Data-Items in one Record that is considered capable of achieving unique and reliable matches against the relevant Data-Items in another Record. The reliability, both generally, and in respect of any particular apparent match, varies greatly, and may be very difficult to estimate.

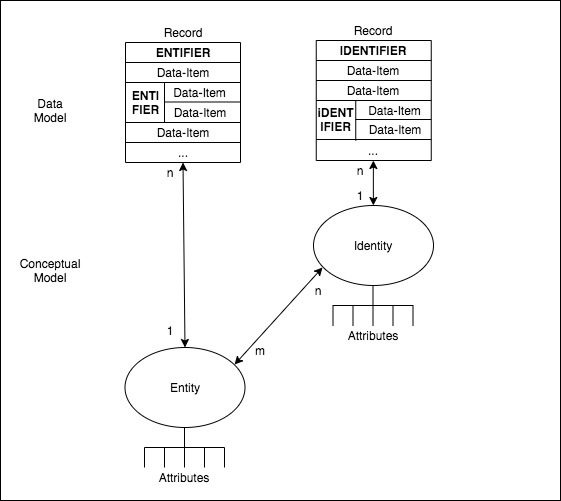

In Figure 2, a visual depiction is provided of the elements of the Conceptual and Data Modelling levels defined so far in this section.

When a Real-World Event occurs, and is reflected in a Conceptual Model-level Transaction, a Record arises, whose function is to cause a change of state in one or more Attributes of one or more (Id)Entities. Means are needed to establish which (Id)Entity-Instances are affected by the Transaction Record. This is achieved by means of (Id)Entification processes.

The term 'Entification' refers to the process whereby Data is associated with a particular Entity-Instance. This involves acquiring or postulating an Entifier that matches with previously-recorded Data-Item-Values. The term exists in some online dictionaries and with a not unrelated meaning, but not in the OED. The term has been used consistently in my work since Clarke (2001), but to date neither it nor, it seems, any equivalent has become mainstream. The emergence of some such term is important, because there are material differences between Identification and Entification, variously conceptually, in terms of the data involved, and in relation to their impacts and implications.

Examples of Entification include the matching of a particular cargo-container's BIC-Code, or a motor-vehicle's VIN, to an existing Record. In addition to such purpose-designed Entifiers, Data-Items of convenience are often relied upon. For example, for computing devices that do not have a reliable, purpose-designed Identifier, the Network Interface Card Identifier (NICId) of, say, the Ethernet card inserted into the computing device, may be used as a proxy. An Ethernet NICId is an example of a multi-data-item Entifier, in that it comprises two Data-Items, an Organizational Unique Identifier (OUI) and a Manufacturer-Serial-No. Dependence on proxies of this nature has varying degrees of reliability.

The acquisition of the Entifier may be by observation followed by either transcription of the data-value by a human, or alternatively by technologically-assisted means such as image-recording using a camera followed by application of optical character recognition (OCR) to extract the value. Another approach is to pre-store the Entifier in a machine-readable form, such as a barcode or a chip, and later use an appropriate technology to extract a copy of that pre-stored data.

The term 'Identification' refers to the process whereby Data is associated with a particular Identity-Instance. This involves acquiring or postulating an Identifier that matches with previously-recorded Data-Item-Values. This application of the term is consistent with dictionary definitions, and has been used in this manner in my works since Clarke (1994b). The term has many other, loose usages, however, particularly as a synonym for 'identifier' (discussed above) or for 'token' or 'authenticator' (both of which are discussed below).

And example of the Identification process in operation is the matching of a SIM-card's ICCID to an existing Record. An example of the use of a Multi-Data-Item Identifier is the recognition of a vehicle on the basis of its properties (such as make, model and colour) at each end of a section of roadway over which average speed is being assessed. Another example is the use, as a proxy Identifier for a particular process running in a computing device, the combination of a port-number and and IP-address, together with (to allow for IP-addresses being 'dynamic', i.e. subject to being re-assigned) a date-range.

From an administrative perspective, (Id)Entification procedures need to be reliable and inexpensive. Achieving that aim can be facilitated by pre-recording an (Id)Entifier on a Token from which it can be conveniently captured. One common form of Token is a card, with the data stored in a physical form such as embossing, or on, or in, a recording-medium such as a magnetic stripe or a silicon chip.

This section has presented the key terms at the Conceptual Model level of Entity, Entity-Instance, and Entity-Attribute; Identity, Identity-Instance and Identity-Attribute; Transaction and Transaction-Instance and Transaction-Attribute; and Relationship, Relationship-Instance and Relationship-Attribute. At the Data Model level, the epistemological notions of Data and Information have been complemented by definitions for the terms Data-Item, Data-Item-Value, Record, File and Meta-Data. Mapping from the Conceptual to the Data Model has been presented as depending on (Id)Entifiers and (Id)Entification processes.

This section has used the simplifying assumption that the Things underlying the (Id)Entities are inanimate, and capable of being treated as mere objects, with minimal concern about the Thing's interests and about clashes among values. The following section relaxes that assumption and considers the additional factors that arise when the underlying Things are people.

The development of the model to this point has limited its focus to inanimate objects and their representations. This has enabled a straightforward, mechanistic approach to be adopted, and values to be left in the background. In many circumstances, animals are also treated as objects. Flies and mice are variously poisoned and injected, and the impacts are rendered as data. Cattle are branded and ear-tagged, and pets have chips injected. On the other hand, animal welfare constraints are placed on handling of vertebrate animals during life and in relation to the manner of death. In some circumstances, data is required by law to be gathered and stored, such as stocking densities for caged chickens and innoculation records, and some forms of animal slaughter are subject to monitoring and data-recording.

Where the Entities being modelled are human beings, additional factors come into play, and hence both the Conceptual and Data Modelling levels need to be adapted in order to reflect those factors. One consideration is the 'free will' or volitional aspect of human beings: inanimate objects do not act of their own accord, and do not have interests that influence their behaviour. In addition, values and rights loom larger when the Entities involved are human beings. The terms 'objectification', in its sense of "the demotion or degrading of a person or class of people ... to the status of a mere object" (OED 2.), and the recent terms 'digitalisation' / 'datafication' / 'datification' (Newell & Marabelli 2015), all carry a pejorative tone when used in respect of people. This is indicative of the fact that the mechanistic application of data-handling notions to humans involves a clash of values between administrative efficiency on the one hand and humanism on the other. This section considers the impact on the modelling approach firstly at the conceptual and then at the data level.

In section 4.1, a series of concepts was discussed and defined. The application of these concept to humans requires care. The notion of human Entity remains, at this stage at least, reasonably uncontroversial, with Entity-Instances confined solely to specimens of the species homo sapiens.

A great many Entity-Attributes are applicable only to human Entities. Some are physiological in nature, such as the person's hair-colour, gender, and date-of-birth or age-range. Others arise from the person's behaviour, such as residential address, qualifications, expertise, and capacity to act as an agent for another Entity-Instance.

Each human Entity-Instance may present many Identity-Instances, to different people and organisations, and in different contexts. The notion of Identity is especially important to humans, because each Entity-Instance (person) plays many roles in many contexts, and these in many cases give rise to separate Identity-Instances. Examples in economic contexts alone include seller, buyer, supplier, receiver, debtor, creditor, payer, payee, principal, agent, franchisor, franchisee, lessor, lessee, copyright licensor, copyright licensee, employer, employee, contractor, contractee, trustee, beneficiary, tax-assessor, tax-assessee, business licensor, business licensee, plaintiff, respondent, investigator, investigatee, and defendant. A similar richness exists in social contexts.

In many circumstances an Identity-Instance is a presentation or role of a single, specific underlying Entity-Instance, e.g. 'I' am the sole 'author of this paper'. On the other hand, some roles are filled by different people, in some cases only serially and in other cases in parallel as well. Examples of serial ambiguity include club treasurer and journal editor-in-chief, and examples of the second include club committee-member, journal senior editor, fire warden, referee and race marshall.

Human Identity-Attributes are related to a particular human Entity's particular presentation or role, rather than to themselves as an Entity-Instance. For example, an eConsumer has a profile comprising such features as demographics and user-interface preferences. People performing roles in organisations inherit authorisations, permissions or privileges. While acting in their manager's absence, a person may be able to sign sick leave forms for their peers, and during an emergency, as fire warden, they can order the CEO's secretary, and even the CEO, to get out of the building. A major issue in data security and in fraud is the phenomenon of individuals abusing powers that they have by virtue of one role that they play, by applying them for extraneous purposes unrelated to that role. The Identity-Attribute commonly referred to as authorisation is accordingly very significant in many IS, and is further discussed in a later section.

In Figure 2 above, Entities and Identities are shown as having a Relationship. The complexities of this Relationship are particularly significant where the Real World Things are humans. Relationship has a Relationship-Attribute of cardinality. Any particular Relationship-Instance may be:

In the case of humans, each Entity-Instance may relate to multiple Identity-Instances (hence 'n'). Further, because each Identity-Instance may be adopted by multiple Entities, the other end of the arrow is marked with an 'm' (equivalent to 'n', but implying that it is a variable independent from the 'n' at the other end of the arrow). For example, the identities association treasurer and editor-in-chief of a particular journal are adopted by multiple people in succession. Others, such as association board-member and senior editor of a journal, may be adopted by multiple people at the same time.

Subtleties in the Relationships between human Entities and Identities need to be well-understood by the designers and users of IS, and reflected in data models and business processes. A particular human Entity-Instance may strongly desire to be the only user of a particular Identity-Instance (e.g. people are very particular about who exercises the capacity to operate on their various bank accounts). Similarly, an organisation may be very concerned that a particular Identity-Instance is used only by one or more specific Entity-Instances (e.g. for the signing of contracts that bind the organisation, and for making statements to the media). It is challenging, however, to prevent use of Identities by other parties. Undesirable activities of these kinds are described by such terms as impersonation, masquerade, spoofing, identity fraud and identity theft.

Transactions represent Real-World Events that give rise to changes in (Id)Entity-Attributes. Events involving humans can be both significant and sensitive, and hence considerable care is needed in the design and processing of such Transactions.

In section 4.2, further (Id)Entity notions were defined at the Data Model level. These too require further articulation where humans are involved.

Because of the high valuation placed on human-ness, many aspects of the manner in which data relating to inanimate objects is handled is inadequate where the data relates to human Entities. Since c.1970, as the collection and management of data about humans exploded under the pressures of increased organisational scale, increased social distance, and increased IT capabilities, a great deal of public concern has arisen about the use and abuse of Personal Data by organisations. Personal-Data-Items vary enormously in their degree of sensitivity. However, no simple formula exists for assessing sensitivity. It is dependent on individuals, their context, and their personal histories and concerns.

To address the concerns that the activities of government and business might be negatively affected by these public concerns, laws relating to 'personal data/information' and 'data protection' emerged. The early, largely nominal protections have proven inadequate to placate an increasingly concerned public. As a result, laws have gone through several maturation phases, with the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) currently seen as the benchmark, and driving further changes in law and practice throughout the world. These laws place considerable constraints on organisations' data-handling activities, and place considerable demands on the nature of the pragmatic model of (Id)Entification and Authentication presented in this paper.

Organisations are confronted with challenges in relation to the collection, storage and use of particular Data-Items (e.g. religion, marital status, ethnicity, disability), and particular Personal Data-Item-Values (age, particular gender-affinities), with (overt) discrimination based on such information, even if demonstrably relevant, precluded by law. There are also constraints on the sources from which organisations can draw Personal Data, and increasing demands for organisations to be able to document the source and demonstrate the quality of Personal Data - which translates into requirements for more and better Metadata.

A form of human Entifier is a biometric. This is a measure of some aspect of the physical person that is unique (or is claimed, or assumed, to be so). Examples include a thumbprint, fingerprints, an iris-pattern and DNA-segments. The uniqueness is not guaranteed. In theoretical terms, some biometric measures are capable of providing a very high probability of uniqueness. On the other hand, the practice of biometrics is far less reliable than theory suggests it might be, because a very substantial set of challenges have to be overcome. In some circumstances, occasional errors may matter very little and/or be easily discovered and corrected. On the other hand, some serious consequences arise from errors, varying from psychological, social and economic harm to some cases as dramatic as conviction and execution of the wrong person.

Another category of human Entifier is usefully referred to as an 'imposed biometric'. Examples include a brand imposed by tattooing or other techniques on a person's skin, and a unique code pre-programmed into an RFID tag that is closely associated with the person, or implanted in them (Clarke 1994d, 1997, 2001a, 2002a).

Common example of human Identifiers include the particular name or name-variant that a person commonly uses in a particular context, such as with family, with a particular group of friends, or when working in a customer-facing role such as a prison officer, psychiatric nurse, counsellor or telephone help-desk. Names are highly variable and error-prone. They do not represent convenient Identifiers for operators of information systems, and are often supplemented by synonym-breakers, such as date-of-birth or some component of address. More effective and efficient business processes can be achieved by means of an organisation-imposed alphanumeric code, such as a customer-code or a username (Clarke 1994d). A human may themselves use many Identifiers including variants of names, and may be assigned many more Identifiers by organisations.

As has been discussed, some Identifiers comprise more than one Data-Item. In rich datasets, however, a large number of multi-data-item Candidate Identifiers may be available. Examples are particularly prevalent in the kinds of data-collections about which most people feel the greatest sensitivity: health data and financial data. Uniqueness can readily arise from unusual medical conditions and postcode of residence. Yet it is precisely these kinds of rich data-collections that are being expropriated by governments obsessed by the 'big data' mantra, and blind to the issues of incommensurable data definitions, a-contextual applications of data, and low data-quality. The camouflage of Personal Data De-identification has been attempted, but rich data-sets are inadequately resistant to Personal Data Re-identification techniques. Personal Data Falsification is necessary if personal values are to be protected against the ravages of collectivist mentalities (Clarke 2019).

The term Nymity refers to circumstances in which the relationship between Entity and Identity is unclear. The term Anonymity refers to a characteristic of an Identity-Instance, whereby it cannot be associated with any particular Entity-Instance, whether from the data itself, or by combining it with other data. In the case of Pseudonymity, on the other hand, association of an Identity with a particular Entity may be achieved, but only if legal, organisational and technical constraints are overcome (Clarke 1999b). In Figure 3, nymity is depicted as an obstacle to the arrow that links the Entity with the Nymous Identity.

Where either form of Nymity applies, it is inappropriate to use the term 'Identifier'. The term Pseudonym refers to a circumstance in which the association between the Identifier and the underlying Entity is not known, but in principle at least could be known. For example, a carefully-protected index may be used to sustain a link between a client-code and the name and address of the AIDS-sufferer to whom the record relates. If an Identifier cannot be linked to an Entity at all, then it is appropriately described as an Anonym. The term Nym usefully encompasses both Pseudonyms and Anonyms.

The term Pseudonym is widely used, and has a large number of synonyms (including aka, 'also-known-as', alias, avatar, character, handle, nickname, nick, nom de guerre, nom de plume, manifestation, moniker, persona, personality, profile, pseudonym, pseudo-identifier, sobriquet and stage-name). In contrast, only a small number of authors have used the term Nym, although it is readily traceable back prior to 1997. Even fewer have used the term Anonym, but it is far from unknown and I have used it consistently in my work since Clarke (2002b).

There are many circumstances in which an Identifier is unncessary and a Nym is entirely adequate. A common example is enquiries in which a set of circumstances is described by the enquirer, and a response is provided explaining the applicability of the law, or of an organisation's policies, to those circumstances. Enquiries are in many cases conducted as a single contiguous conversation. However, it is also possible for multiple, successive interactions to be connected with one another by means of a Persistent Nym. A celebrated example of a Persistent Nym is the whistleblower who brought US President Nixon undone. 'Deep Throat' remained a Persistent Anonym from 1974 until 2005. 'Publius', which was used for contributions to debates about the U.S. Constitution, was a Persistent Anonym at the time, and has remained an Anonym since 1787.

A frequently-encountered phenomenon in recent decades has been efforts by organisations to achieve linkage among Identifiers, in order to be able to associate, compare and even consolidate data-holdings in multiple collections, often across multiple organisations. When data silos are compromised or destroyed, the correlation, matching, consolidation or merger of separate records is undertaken on the basis of one or more Identifiers, such as name and date of birth, or commonly occurring identifying codes. Although some of these consolidation activities have benefits for individuals, they mostly address the needs of organisations. Historically, the notion of Identity Silo - the storage of data in an independent data-collection, for specific purposes - has been one of the strongest protections for human values. (The term is my own coinage, in consistent use since Clarke 2006. It is a natural extension of the established data silo notion, but has not at this stage come into common usage). The breaking down of Identity Silos represents the destruction of one of the most potent forms of data privacy protection, and hence is a major contributor to the collapse in organisational trustworthiness, and to public nervousness about manipulation of individuals' behaviour by governments and corporations alike.

An alternative approach to correlation among Identifiers is the use of Multi-Purpose Identifier. A common example is national registration numbers assigned to residents in many European countries, which are used within some cluster of related functions such as taxation, health insurance and self-funded pensions (also referred to as national insurance or superannuation). A General-Purpose Identifier, such as the national identity number that is imposed on the residents of countries such as Denmark, Estonia and Malaysia, is intended to enable the consolidation of all of an Entity-Instance's multiple Identity-Instances, complete the destruction of Identity Silos, deny the possibility of Nymity, and thereby provide the State, individual agencies and individual corporations with far greater power over the people they deal with (Clarke 1994d, 2006).

Entification refers to the process whereby Data is associated with a particular Human Entity-Instance. This depends on the acquisition of an Entifier such as a biometric, or an imposed biometric such as an implanted chip. All forms of biometric acquisition are highly personal and threatening, and many are demeaning. For example, high-quality recording of a thumbprint or fingerprints involves a skilled operator grasping the person's wrist and controlling the hand's movement, and iris-scans and retinal-scans involve submission of the body to whatever device the measuring organisation imposes on the individual. Moderate-quality recordings of those biometrics results in far higher incidence of error and hence mistaken identity, whose negative impacts will commonly fall on the individual. Pre-stored Entifiers pre-stored on a Token such as a chip-card can be captured in a technologically-assisted or -performed manner. However, that greatly increases the risk of the Entifier being associated with the wrong person.

Pastoralists have had no qualms about clipping RFID-cards onto the ears of entire herds of stock-animals. Pet-owners have regarded the injection of chips into their beloved animals because they perceive it to increase the chances of a lost pet being returned to its owner. The same approaches, however, have historically excited revulsion when applied to humans. Early applications to humans have included chips in 'anklets' for convicts, and even remandees, in 'prisons without walls', in military 'dog-tags' to assist the identification of combat casualties, and in patient-tags to assist in ensuring that operations are performed on the right person; and chips injected into the bodies of staff in research facilities, and customers of fashionable bars, who want doors to open automatically for them. On the other hand, considerable concern has been expressed about Tokens imposed on the aged, and the insertion of chips into the tooth-enamel of children to identify victims of kidnapping and abduction was not attractive to parents. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent human values will be infringed through this form of objectification of individuals.

Identification refers to the process whereby Data is associated with a particular Identity-Instance, in this case an Identity-Instance used by a human. It involves the acquisition of an Identifier, such as a name or a customer number. This may be provided by the person concerned, by voice, by displaying a Token such as a membership card, or by making a Token available that contains a pre-stored Identifier capable of being read by a device operated by an organisation.

IS are designed to assist organisations in administering their interactions with humans by recording Data-Item-Values for relevant (Id)Entity-Instances. The Data-Item-Values for each particular (Id)Entity-Instance are stored in a Record that contains one of more of their Entifiers or Identifiers. Data-Item-Values contained in each new Transaction can be used to locate the appropriate Record on the basis of an (Id)Entifier that the Transaction contains. On that basis, decisions can be made, actions taken, and amendments made to the Record for that person.

During the early decades of IS, the primary source of organisations' Data about individuals was Transactions between that organisation and the individual concerned. Since the late 20th century, however, organisations have increasingly drawn Data from multiple, additional sources, and consolidated it into individuals' records. The reliability of the association, the potential conflicts among meanings of apparently similar Data-Items, and the nature of the original collection and subsequent handling, ensure that there is a great deal of doubt about data-quality standards in such circumstances. The degree of expropriation of Personal Data has intensified enormously since the emergence of the Digital Surveillance Economy c.2005. This commenced with the inversion of the originally user-driven World Wide Web by means of Web 2.0 technologies, and the explosion of social media (Zuboff 2015, Clarke 2019).

The term Digital Persona refers to a model of an individual's public personality based on Data and maintained by Transactions, and intended for use as a proxy for the individual. In practical terms, it is a collection of Data stored in a Record that is rich enough to provide an organisation with an adequate image of the represented Entity or Identity. The term is my own coinage, first presented at the Computers, Freedom & Privacy Conference in San Francisco (Clarke 1993), and published in Clarke (1994a, 1994b). But it is in any case an intuitive term and has gained some degree of currency (Clarke 2012). It is quite common to see the term 'identity' used to refer to what is called here a Digital Persona; but 'identity' has many meanings, and to avoid ambiguity it is far preferable that some other term be used. Another candidate term is e-persona. The term 'partial' (which originated in the sci-fi genre) is also a contender, because it underlines the inherent incompleteness of a digital persona in comparison with the real-world entity or identity it represents.

[ More from http://rogerclarke.com/DV/DigPersona.htm

Imposed cf. projected; formal cf. informal; passive cf. active and autonomous

A Projected Digital Persona is under the control of the individual, and is fundamental to an individual's sense of self and self-esteem. It is vital to all kinds of performance art, from stage acting to job interviews and social media imagery and influencing. It enables individuals to achieve a safe space in which they can indulge in psychological game-playing (e.g. using handles and avatars), cultural creativity (e.g. using stage-names and noms de plume), inventive and innovative behaviour of a technical and economic nature, whistleblowing to expose waste, hypocrisy and corruption, and political opinion and dissent. The Projected Digital Persona is, of course, also exploited for criminal purposes, including the avoidance of Identification and the performance of various kinds of misleading behaviour that may be subject to civil and criminal sanctions, such as false rumours, 'alternative facts', defamation, deceptive commercial conduct and fraud.

An active Projected Digital Persona is capable of taking actions as an agent for the individual. An agent may be as simple as an auto-responder to emails, or as complex as a bot that conducts social interactions intended to create and maintain a Digital Persona radically different from the individual it nominally represents. An active agent may have varying degrees of autonomy. A Projected Digital Persona may constructively misrepresent the individual, to the point of in effect creating a pseudo-individual - an Identity-Instance with a very loose association with one or more underlying Entity-Instances. This may be done for psychological purposes as a form of self-defence or self-entertainment (an alter ego), or for social entertainment (as in role-playing in games), or as a means to obfuscate and falsify the person's profile to avoid manipulation by marketing organisations, or as a means conducting criminal behaviour while avoiding being identified by law enforcement agencies.

An Imposed Digital Persona is controlled by someone other than the individual it is associated with. From the outset, it was clear that there was scope for active Imposed Digital Personae to "[enable] people's interests or proclivities [to] be inferred from their recent actions, and appropriate goods or services offered to them by the supplier's computer program using program-selected promotional means" (Clarke 1994a, p. 83). This idea came into the mainstream from 2005 onwards, and forms the basis of the business model used by social media corporations. The term Digital Persona was applied soon after its coinage by IT industry CEO, Eric Schmidt (Adams 1997). Within a few years, Schmidt became CEO and later Chair of Google, and was one of key drivers of the Digital Surveillance Economy.

Every Digital Persona is a simplification of a complex reality; and because it is incomplete, its use embodies a risk of mis-judgement. A Digital Persona is constructed from multiple sources, and because those sources are imperfectly compatible, 'artefacts' may result, i.e. unwarranted inferences may be drawn about the individual associated with the Digital Persona. Added to that, although an Imposed Digital Persona may be known to the individual it is used to represent, it is very common for it to be used in covert fashion, and to be not merely inaccessible by the person concerned, but unknown to them.

In one sense, consumers might be pleased that marketing corporations are mis-reading them. On the other hand, search-services bias the sequence in which results are displayed based on the Digital Persona, and hence all forms of discovery are compromised and the service to consumers materially degraded. Dealings with government agencies are particularly problematic, because the risk of wrong and unreasonable decisions can be high, the risk is borne by the individual not the agency, and prosecuting innocence is near-impossible, particularly where the Imposed Digital Persona is covert, and the content that constitutes it is inaccessible to the person. The nature of the accusation is consequently unclear, in a manner related to Kafka's 'The Trial'.

The mobilisation of resources at scale depends on large groups acting in a coordinated fashion. Contemporary societies use many different organisational forms. The law recognises them as 'legal persons', and in some common law countries 'bodies politic' or 'bodies corporate'. In either case, they are independent from the individuals who call them into being and who are from time to time their directors, members and employees.

Organisations present a challenge to the application of the pragmatic model of (Id)Entity. Organisations are in some sense an Entity, but, unlike both objects and humans they lack corporeal, Real-World form, and unlike humans they lack the capacity to act in the Real-World. On the other hand, they are accepted in law and practice as having existence, and having the capacity to make decisions, act in the Real-World, bear responsibilities and incur liabilities.

The approach adopted here is to recognise organisations as Virtual Entities, with Attributes and Relationships, that may present many Identities, to different people and organisations, and in different contexts, including as customer, supplier, employer and contractor. Organisational (Id)Entities are distinguished by means of many (Id)Entifiers, in particular names (e.g. associated with business units, divisions, branches, trading-names, trademarks and brands), and numbers and codes assigned by other Entities. A key requirement, however, is that organisational (Id)Entities must have Relationships with other (Id)Entities, which are of a principal-agent nature, whereby the organisational (Id)Entity delegates powers to decide and act, and, with that, relevant parts of its responsibilities, to human (Id)Entities.

With the ongoing developments in the sophistication of artefacts, the scope must also be recognised for powers to be delegated to Active-Artefact Entities (robots) and Active-Artefact Identities (computing processes). Debate has commenced about accountability for the outcomes of acts performed or caused to be performed by active-artefact (Id)Entities. The century since Capek invented the word 'robot' has seen those concerns about their capabilities migrate from artistic imagination to technological prospect. The artistic notion of a species of robots is associated with Capek a century ago, and articulated by Asimov and then Arthur C. Clarke, 1940-1990. Surprisingly, however, the earliest use of the term roboticus sapiens appears to be in (Clarke 2014). Many people have great difficulty with the notion that an organisation or a human could be permitted to avoid responsibilities by delegating them to an artefact. The approach adopted in the pragmatic model is that organisational and human (Id)Entities may delegate powers to artefact (Id)Entities, but they can neither delegate nor escape responsibilities associated with, or arising from, the exercise of those powers.

At various points in the exposition of the model, reference has been made to assertions about Data, about (Id)Entities, about the capacity of a particular (Id)Entity to act on behalf of another (Id)Entity. That leads to the question of what evidence supports these assertions. A companion paper applies the pragmatic model developed in this paper to the matter of authentication of assertions (Clarke 2021c).

[ From http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-App-1002.html

TEXT, authorisations, permissions, privileges

This is being developed in a related project, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/IQLO.html

[ Check against http://rogerclarke.com/EC/AuthModel.html#Model

[ Check against http://rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled03.html

Public Key Infrastructure?

Biometrics?

TEXT

Adams B. (1997) '' Deseret News, 20 November 1997, at http://www.deseretnews.com/article/595933/Novell-introduces-goal-putting-a-friendly-face-on-computer-networking.html?pg=all

Chen P.P.S. (1976) 'The Entity-Relationship Model - Toward a Unified View of Data' ACM Transactions on Database Systems 1 (March 1976) 9-36

Clarke R. (1993) 'Computer Matching and Digital Identity' Proc. Computers Freedom & Privacy, Burlingame CA, March 1993, at http://cpsr.org/prevsite/conferences/cfp93/clarke.html/, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/CFP93.html

Clarke R. (1994a) 'The Digital Persona and its Application to Data Surveillance', The Information Society 10, 2 (June 1994)', at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/DigPersona.html

Clarke R. (1994b) 'Human Identification in Information Systems: Management Challenges and Public Policy Issues' Information Technology & People 7,4 (December 1994) 6-37, at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/HumanID.html

Clarke R. (2001a) 'Authentication: A Sufficiently Rich Model to Enable e-Business' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, December 2001, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/AuthModel.html

Clarke R. (2001b) 'The Re-Invention of Public Key Infrastructure' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 22 December 2001, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/PKIReinv.html

Clarke R. (2003) 'Authentication Re-visited: How Public Key Infrastructure Could Yet Prosper' Proc. 16th Int'l eCommerce Conf., Bled, Slovenia, 9-11 June 2003, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled03.html

Clarke R. (2010a) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation' Proc. IDIS 2009 - The 2nd Multidisciplinary Workshop on Identity in the Information Society, LSE, London, June 2009, rev. February 2010 at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010b) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Supplementary Materials' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-Supp-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010c) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Glossary of Terms' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-Gloss-1002.html

Clarke R. (2010d) 'A Sufficiently Rich Model of (Id)entity, Authentication and Authorisation: Application of the Model' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, February 2010, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IdModel-App-1002.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'Promise Unfulfilled: The Digital Persona Concept, Two Decades Later' Information Technology & People 27, 2 (Jun 2014) 182 - 207, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/ID/DP12.html

Clarke R. (2014) 'What Drones Inherit from Their Ancestors' Computer Law & Security Review 30, 3 (June 2014) 247-262, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/Drones-I.html

Clarke R. (2019) 'Risks Inherent in the Digital Surveillance Economy: A Research Agenda' Journal of Information Technology 34, 1 (March 2019) 59-80, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/DSE.html

Clarke R. (2021) ' A Pragmatic Metatheoretic Model for Information Systems Practice and Research' Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, May 2021, at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/POEisy.html

Newell S. & Marabelli M. (2015) 'Strategic Opportunities (and Challenges) of Algorithmic Decision-Making: A Call for Action on the Long-Term Societal Effects of 'Datification'' The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 24, 1 (2015) 3-14, at http://marcomarabelli.com/Newell-Marabelli-JSIS-2015.pdf

Zuboff S. (2015) 'Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization' Journal of Information Technology 30, 1 (March 2015) 75-89, at https://cryptome.org/2015/07/big-other.pdf