Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

For the

International

Digital Security Forum (IDSF22)

Vienna, 1 June 2022

Stream on 'Understanding the Challenges of Digital Societies'

Discussion Draft of 13 May 2022

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2022

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/MSRA-VIE.html

The supporting slide-set is at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/MSRA-VIE.pdf

Interventions into social systems are of various kinds, including new and amended laws, variations in institutional structures and processes, and technological innovation. Social systems inevitably feature multiple participants, and significant interventions into social systems have impacts on most of them. Interventions also affect parties outside the system itself. Such parties are conveniently referred to as 'usees', to distinguish them from participants or 'users'. Participants and usees alike have interests, and each of them seeks to promote and defend those interests.

During the rational management era, since the mid-20th-century, various procedures have been used to assess the likely outcomes of interventions. These include business case development, net-present-value analysis, cost-benefit analyis, risk assessment, and impact assessment.

Most procedures used by organisations effectively treat the interests of that organisation as paramount, and relegate the interests of other participants and usees to the role of constraints on the achievement of the organisation's objectives. Such approaches as technology assessment, environmental impact assessment and privacy impact assessment, on the other hand, tend to adopt a broader view.

This paper seeks a practicable mechanism whereby the interests of participants and usees can be reflected in the assessment of interventions. Existing theory and practice are drawn on, and options outlined. A particular approach is described, referred to as Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA), and examples provided of real-world instances that evidence some of the features of MSRA.

The broad theme of this event is 'digital security'. As in all discussions of the notion of security, confusion and misunderstanding will be rife unless clear statements are made about 'security of what, against what, and for whom?'. The conference theme permits many interpretations, some involving 'security of digital infrastructure or processes', others with a focus on 'security against digital infrastructure or processes', and in both cases with a wide range of potential beneficiaries and victims.

This paper considers the effects of interventions involving or affecting structures and processes in digital society. Interventions can of course be of many kinds, including new or amended legislation, regulatory measures of some other nature, adaptation of institutional or sectoral infrastructure, particularly due to shifts in market power, changes in business processes, and new forms and new applications of transformative or disruptive technologies.

Interventions of scale or other significance may or may not deliver the 'obvious' or expected or intended outcomes. Added to that, they may have substantial first-order impacts, and particularly second-order implications, that were unforeseen by the intervention's proponents. It is therefore widely recognised that the impacts and implications of interventions require evaluation. A wide variety of evaluation techniques exists. Mainstream techniques applied by business enterprises include business case development and risk assessment. Techniques with broader scope include cost/benefit analysis and technology assessment.

The analysis reported in the present paper is concerned with security of the interests of stakeholders of all kinds against interventions, and particularly interventions involving technologies. Some evaluation techniques have a very tight focus on the interests of a single stakeholder, whereas other approaches are more amenable to consideration of the concerns of multiple players. The paper's purpose is to seek a practicable mechanism whereby the interests of relevant players can be reflected in the assessment of interventions.

The paper commences by summarising key insights from stakeholder theory. This enables consideration of the extent to which each of the variety of evaluation techniques is capable of reflecting the interests of multiple users. An alternative with promise is argued to be an adapted form of the conventional and well-documented business approach of risk assessment. As a preliminary test of the proposition, some exemplars of such an approach are identified.

The term 'stakeholders' was coined as a counterpoint to 'shareholders', in order to bring into focus the interests of parties other than the corporation's owners (Freeman & Reed 1983). In IT contexts, users of information systems have long been recognised as stakeholders, commencing in the 1970s with employees. With the maturation of inter-organisational and then extra-organisational systems (Clarke 1992), IT services extended beyond organisations' boundaries, and hence many suppliers and customers, both corporate and individual, became 'users' as well.

The notion of 'stakeholders' is broader than just users, however. It comprises not only participants in information systems but also "any other individuals, groups or organizations whose actions can influence or be influenced by the development and use of the system whether directly or indirectly" (Pouloudi & Whitley 1997, p.3). The term 'usees' is usefully descriptive of such once-removed stakeholders (Berleur & Drumm 1991 p.388, Clarke 1992, Fischer-Huebner & Lindskog 2001, Wahlstrom & Quirchmayr 2008, Baumer 2015).

The stakeholder notion has been subjected to further analysis and discussion during the almost four decades since it emerged. One analysis distinguishes stakeholders on the basis of power, legitimacy and urgency (Mitchell et al. 1997).

Much as an approach based on ethics might dictate that 'legitimacy' has primacy, a strong tendency has been evident, in industry and government practice alike, to pay attention to the interests of only those stakeholders that are capable of significantly affecting the success of the project - as perceived by the project sponsor. The interests of that organisation are treated as paramount, and the interests of other participants and usees are relegated to the role of constraints on the achievement of the primary organisation's objectives. All but the most powerful participants are thereby marginalised (Achterkamp & Vos 2008).

A wide range of evaluation techniques exists, with widely varying approaches and foci. This analysis excludes consideration of activities that are merely concerned with checking an organisation's compliance with 'soft' regulatory instruments (such as codes of ethics and industry standards), or with a statute or delegated legislation such as a formal Code, or with a broad body of law (such as safety, data privacy or consumer rights).

Mainstream techniques within organisations include Business Case Development (BCD, Schmidt 2005), Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (DCF, SoW 2013) and Net Present Value Analysis (NPV, Dikov 2020), financial sensitivity analysis and financial risk assessment. All of these depend on quantification, and in particular on the expression of costs and benefts in financial terms. The analysis is generally undertaken from the perspective of a single legal entity or government agency. In the case of interventions in which technology plays a major role, that organisation is typically the system sponsor.

Some single-organisation assessment techniques extend to factors that cannot be readily reduced to financial values, whose representations are referred to as 'non-quantifiable' or 'qualitative' data. These approaches include internal Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA, Stobierski 2019) and Risk Assessment (RA), which is further discussed below. All of these techniques are highly organisation-centric, and only reflect interests of some other party if that stakeholder is perceived by the organisation to be sufficiently powerful to be able to affect the organisation's capacity to achieve its purposes.

Some other techniques have a much broader frame of reference. Technology Assessment (TA) is concerned with the evaluation of potential impacts and implications of a particular technical capability (OTA 1977, Garcia 1991). Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA, Morgan 2012) is an approach that evaluates the effects on the physical environment (air, land and water) of a development project such as a mine, a dam, transport infrastructure, a manufacturing facility, a built-up area or even a single large building. Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) considers effects on individuals' privacy interests - although often only the privacy interests involved in personal data (Clarke 2009, Wright & de Hert 2012). Social impact assessment (Becker & Vanclay 2003) has a broader remit, and surveillance impact assessment (Wright & Raab 2012, Wright et al. 2015) combines technological with psychological and social impact assessment.

It is feasible to apply some such form of impact assessment approach in order to address the concerns of particular stakeholders. However, the approach is seldom consistent with any particular organisation's perceived needs, and is in direct conflict with the legal responsibility of Board directors to serve the interests of shareholders. Moreover, it demands considerable depth and breadth of analysis and hence considerable resources with specialist expertise.

The approach that appears to offer the best prospects is risk assessment. An industry standard is published as ISO 27005:2011. See also, for example, NIST (2012), EC (2016).

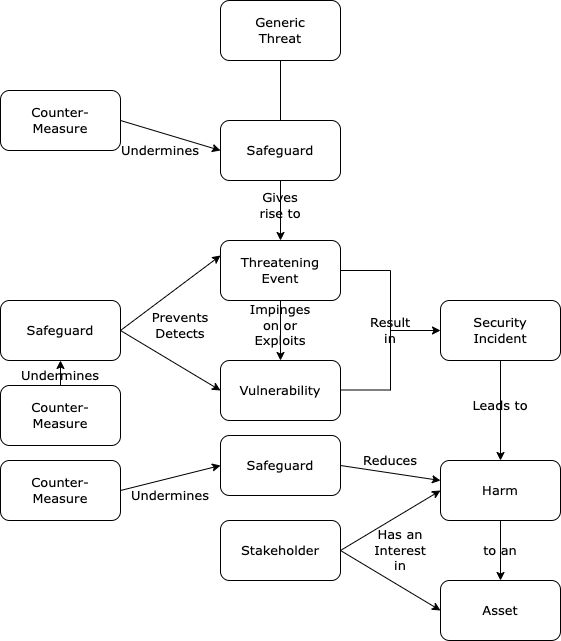

The assessment of risk needs to be based on a model of security, and on a set of terms with sufficiently clear definitions. In the sub-area of data security, a substantial literature exists, and this provides a useful framework that can be drawn on in other contexts. A depiction of the conventional security model is in Exhibit 1.

Briefly, threatening events impinge on vulnerabilities, resulting in security incidents that may give rise to harm to assets. Safeguards provide protections against threatening events, vulnerabilities and harm. Security is a condition in which harm is in part prevented, and in part mitigated, because threats and vulnerabilities are subject to safeguards that withstand countermeasures. The terms are defined in Appendix 1.

Extract from Clarke (2015, p.547-549)

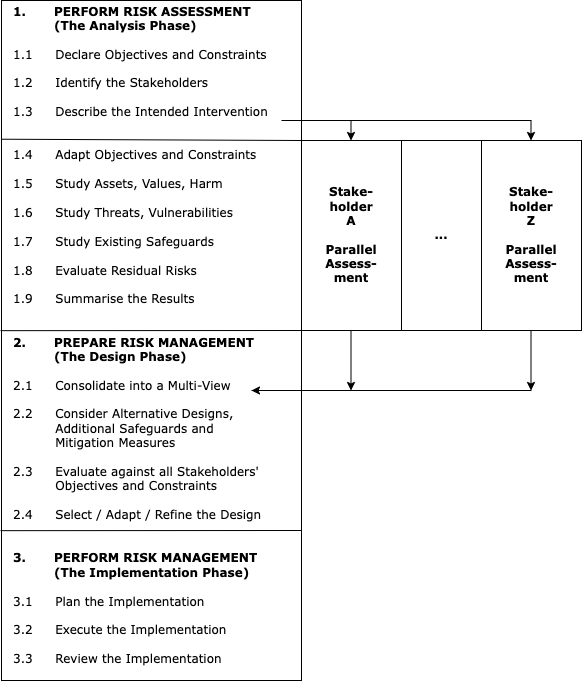

The conventional Risk Assessment process uses a short sequence of steps to apply the concepts in Exhibit 1 in order to identify and understand residual, inadequately-addressed risks, and hence lay the foundation for Risk Management activities to address them.

The RA technique was conceived to serve the interests of the organisation that conducts the evaluation, or that commissions the work to be performed. Standards documents and most guidelines for performing the technique reflect those origins. On the other hand, I argued in Clarke (2019, p.413), in the specific context of Artificial Intelligence (AI), that:

In this paper, I argue that those assertions apply not only to applications of Artificial Intelligence, but also to technologically-based interventions generally: RA is capable of adaptation to accommodate stakeholders additional to the system sponsor.

In Exhibit 2, a depiction is provided of a conventional, organisation-internal RA process, extended to encompass multiple, parallel assessments, all of which draw on a common base of information, but each of which is undertaken from the perspective of a particular stakeholder. The results of the various assessments need to be then integrated into a consolidated multi-view. That multi-view then needs to be applied during the design and implementation phases in order to manage the identified risks.

Further Development from Clarke (2019, p.414)

In Clarke (2019), the term 'Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment' (MSRA) was applied to this technique. Although it is a straightforward descriptor, searches of previous usage in the refereed literature have found only a few casual uses of the expression, of which Molarius et al. (2016) appears to be the most relevant. The term 'Multi-Stakeholder Risk Management' (MSRM), applicable to the subsequent phases in which the consolidated multi-view is applied, has also put in a small number of appearances in the literature, notably in Young & Jordan (2002) and Shackelford & Russell (2016).

MSRA could serve the interests of stakeholders additional to the system sponsor in at least two ways, which are outlined in the following two sub-sections.

One approach would be for a risk assessment process to be performed by each relevant category of stakeholders, or by some collaboration, collective, advocacy organisation or proxy representing the interests of the relevant category. However, each activity requires information, and adequate human resources with the relevant expertise; and multiple such undertakings would need to be conducted.

The asymmetry of information, resources and power, and the degree of difference in world-views among stakeholder groups, is commonly so pronounced that the results of such independent activities are difficult to communicate to other players with materially different world views. The results appear unlikely to be assimilated by the system sponsor, and integrated into the organisation's ways of working.

In short, only those stakeholders with sufficient market power are likely to be able to force the system sponsor to recognise the legitimacy of their claims. In any case, all are readily played off by the system sponsor, who can portray them as being in competition with one another rather than having substantial commonality of interest.

The chances of the promise of MSRA bearing fruit may be much better where each of the parties perceives advantages to themselves in gaining an understanding of the various perspectives and, to the extent feasible, accommodating the interests of all other parties.

The technique could achieve traction where the system sponsor recognises that it is advantageous to drive the parallel studies and engage directly with the relevant parties. The organisation can gain sufficiently deep understanding, and can reflect stakeholders' needs in the project design criteria and features. Moreover, it may be able to do so without bearing disproportionate cost, and with harm to its own interests kept within manageable bounds.

A second circumstance in which a multi-pronged risk assessment approach could be feasible is where the system sponsor adopts it for 'business ethics', 'corporate social responsibility' or 'public policy' reasons. This appears most likely in circumstances where the institutional context reinforces collaborative and human-wellbeing values. For example, the system sponsor may be a public agency whose mission is to deliver particular economic and/or social value to particular citizen segments. Alternatively, the system sponsor may be working under a government grant or contract, or may be a joint venture in which at least some of the participating organisations recognise a social-responsibility imperative.

A third possibility exists. A requirement could be imposed on a system sponsor to reflect the interests of multiple stakeholders, with a sufficiently credible threat of enforcement action to motivate compliance. Apart from formal statutory authority, such a requirement might derive from the institutional environment, such as licensing conditions, or 'moral suasion' by a powerful regulatory agency, or perhaps just cultural conventions within the industry sector or country.

The argument presented above has been almost entirely theoretical, with little evidence of practical application, let alone of economic and social drivers that could bring the ideas to fruition. This section tests whether the proposition has potential, by seeking out circumstances in which at least some of the characteristics of MSRA are apparent.

In many countries, large-scale interventions into the landscape are subject to substantial, formal and cumbersome procedures. Where the intervention is less dramatic, but is impactful, or is perceived or is feared to be so, the sponsor may find it necessary, advisable or advantageous to conduct an MSRA in order to identify and understand the concerns of the various interest groups. An example might be a facility that handles chemicals, such as a fire station, being developed or extended adjacent to, or upstream from, a lagoon that harbours frogs and whose surrounds are used for children's leisure activities.

Where a mining company wants to extract ore from an area that is in a reserve, or is subject to laws conferring some form of native title, it may need to negotiate with indigenous groups. If the company wants to get to grips with the possibly diverse, complex and/or vague concerns of such groups, the multi-stakeholder risk assessment approach may be an attractive tool.

During a period when decentralisation was in vogue, a government agency may have established an operational facility in a regional city or town. It may have been, or gradually become, a significant employer in the district. The time may come to close the facility, particularly if it performs functions that have been overtaken by technological innovation, such as bulk printing-and-posting or the scanning of manual forms arriving in the post. The agency may find it politically necessary to conduct an assessment of the impact of closure, taking into account the circumstances of many segments of society, and both economic and social effects. A large corporation for which public image is important may also find it advisable to adopt a process of this nature.

Medical implants may provide good exemplars of multi-stakeholder risk assessment and management. The industry involves designers undertaking carefully-designed pilot studies, with active participation by multiple health care professionals, patients, and patient advocacy organisations.

A government might seek to break open a monopoly marketspace, perhaps through legislation or moral suasion. Such an intervention may be designed to restructure the institution and change its business processes, probably taking advantage of technology, in order to balance the interests of the parties involved in it, and the parties dependent on it. An MSRA might be an effective means of exposing the impacts of the current arrangements, gaining public support, and shaming the current beneficiaries into accepting the need for change. An example in the livestock industry was the hog auction market in Singapore (Neo 1992).

In the 1980s, Australian livestock producers, distant from major population-centres, faced high costs to get their stock to saleyards, and low prices offered for their product by well-informed agents for supermarket chains, in so-called 'farm-gate private treaties'. The problem-definition process reflected the principles intrinsic to MSRA. The producers' association then developed an early online auction scheme, the computer-aided livestock marketing (CALM) system. Supported by a newly-created class of certified stock inspectors, the scheme published the prices paid for various stock-categories nationwide. The result was reduced information asymmetry in the marketspace, and a better balance among the market-participants' interests (Clarke & Jenkins 1993).

Industry sectors such as health, international trade, and major infrastructure such as sea-ports and airports, are not organised as linear supply-chains, nor in a hub-and-spoke or star configuration. They feature many specialised enterprises, and many inter-linkages and flows among those enterprises, overlaid by considerable regulatory interference to satisfy such public-interest needs as safety, hygiene, service quality and tax-collection. Changes to architecture, infrastructure, data flows and business processes need to take into account the interests of a wide range of participants and beneficiaries. MSRA has attributes that satisfy some of those needs (Clarke 1994, Cameron 2009).

A particular form of sectoral transformation is commonly referred to as the 'technology platform' model. Disruptors such as eBay (since 1995), booking.com (1996), Expedia (1996), Tripadvisor (2000), Mechanical Turk (2005), YouTube (2005), Airbnb (2008), Freelancer.com (2009), Pinterest (2009) and Uber (2009) have taken advantage of new technology and their lack of any legacy technology or labour force, by deploying new services at a speed that large, established, and in many cases highly-regulated corporations simply cannot replicate.

The profiles of some of these platforms include two additional features. One is long-term under-cutting of existing markets, linked with loss-leadership, and supported by low-paid piece-workers and ever-growing investment based on the assumption of future super-profits. The other is a deep disregard for the laws that apply to the sector that the innovator is determined to redefine. Case studies have highlighted abject failure by regulatory agencies to enforce those laws, in many jurisdictions ( Wyman 2017, Clarke 2022). The dislocation and financial losses suffered by investors and employees alike would have been mitigated had a multi-stakeholder risk assessment been undertaken and a transition strategy designed to enable progress without such dramatic negative consequences.

Interventions have short-term impacts and medium-term implications. Large-scale and otherwise impactful interventions need to be evaluated not just implemented. Many assessment techniques have a tight focus on the interests of the system sponsor. There are few drivers for multi-stakeholder assessment. To the extent that other stakeholders' interests are reflected, it is because those particular parties have sufficient power.

Inevitably, stakeholders that merely have legitimacy and/or urgency suffer depradations from interventions, because the interventions' sponsors are not attuned to their interests. In many cases, harm to their interests could have been avoided, or at least mitigated, and even some benefits delivered, with only limited compromise to the sponsor's objectives, if their needs had been factored into the design.

Even if the will exists to reflect stakeholders' legitimacy as well as their power, there are challenges in finding suitable evaluation techniques to apply. Business Case Development is driven by the prospects of profit. Most of the variants of Impact Assessment concern themselves with particular categories of effect that interventions may have. Technology Assessment, concerned as it is with a broad technology with many capabilities, which may give rise to a variety of interventions into economic and social systems, tends to be highly informative, but its influence is dissipated across many contexts.

The choice may seem strange, but the well-developed technique of Risk Assessment - a creature of rational enterprise management - may harbour the best prospects for reflecting the interests of multiple stakeholders. Preliminary testing of the Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA) technique, by searching for contexts in which some of its hallmarks are evident, identifies a variety of exemplars. Further experimentation and trialling is necessary, to establish whether it can fulfil the need.

Achterkamp M.C. & Vos J.F.J. (2008) 'Investigating the use of the stakeholder notion in project management literature, a meta-analysis' Int'l J. Project Management 26, 7 (October 2008) 749-757

Baumer E.P.S. (2015) 'Usees' Proc. 33rd Annual ACM Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI'15), April 2015

Becker H. & Vanclay F. (2003) 'The International Handbook of Social Impact Assessment' Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2003

Berleur J. & Drumm J. (Eds.) (1991) 'Information Technology Assessment' Proc. 4th IFIP-TC9 International Conference on Human Choice and Computers, Dublin, July 8-12, 1990, Elsevier Science Publishers (North-Holland), 1991

Cameron J. (2009) 'An integrated framework for managing eBusiness collaborative projects' PhD Thesis, UNSW, September 2009, at https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/13ce09cb-ee14-456c-87a3-5e7547a4a2e4/full

Clarke R. (1992) 'Extra-Organisational Systems: A Challenge to the Software Engineering Paradigm' Proc. IFIP World Congress, Madrid, September 1992, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/PaperExtraOrgSys.html

Clarke R. (1994) 'EDI in Australian International Trade and Transportation' Proc. 7th EDI-IOS Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 6-8 June 1994, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled94.html

Clarke R. (2009) 'Privacy Impact Assessment: Its Origins and Development' Computer Law & Security Review 25, 2 (April 2009) 123-135, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAHist-08.html

Clarke R. (2015) 'The Prospects of Easier Security for SMEs and Consumers' Computer Law & Security Review 31, 4 (August 2015) 538-552, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/SSACS.html#App1

Clarke R. (2019) 'Principles and Business Processes for Responsible AI' Computer Law & Security Review 35, 4 (2019) 410-422, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/AIP.html

Clarke R. (2022) 'Research Opportunities in the Regulatory Aspects of Electronic Markets' Electronic Markets 32, 1 (Jan-Mar 2022), PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/RAEM.html

Clarke R. & Jenkins M. (1993) 'The strategic intent of on-line trading systems: a case study in national livestock marketing' Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2, 1 (March 1993) 57-76, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/CALM.html

Dikov D. (2020) 'Using the Net Present Value (NPV) in Financial Analysis' Magnimetrics, 2020, at https://magnimetrics.com/net-present-value-npv-in-financial-analysis/

EC (2016) 'EU general risk assessment methodology' European Commission, 2656912, June 2016, at https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/17107/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

Fischer-Huebner S. & Lindskog H. (2001) 'Teaching Privacy-Enhancing Technologies' Proc. IFIP WG 11.8 2nd World Conference on Information Security Education, Perth, Australia, 2001

Freeman R.E. & Reed D.L. (1983) 'Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance' California Management Review 25, 3 (1983) 88-106

Garcia L. (1991) 'The U.S. Office of Technology Assessment' Chapter in Berleur J. & Drumm J. (eds.) 'Information Technology Assessment' North-Holland, 1991, at pp.177-180

ISO 27005:2011 'Information technology--Security techniques--Information security risk management' International Standards Organisation, 2011, especially pp. 7-17 and 33-49

Mitchell R.K., Agle B.R. & Wood D.J. (1997) 'Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts' Academy of Management Review 22, 4 (1997) 853-886

Molarius R., Raeikkoenen M., Forssen K. & Maeki K. (2016) 'Enhancing the resilience of electricity networks by multi-stakeholder risk assessment: The case study of adverse winter weather in Finland' Journal of Extreme Events 3, 4 (2016)

Morgan R.K. (2012) 'Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art' Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30, 1 (2012) 5-14, at https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.661557

Neo B.S. (1992) 'The implementation of an electronic market for pig trading in Singapore' Journal of Strategic Information Systems 1, 5 (December 1992) 278-288

NIST (2012) 'Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments' US National Institute for Standards and Technology, SP 800-30 Rev. 1 Sept. 2012, pp. 23-36, at https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-30/rev-1/final

OTA (1977) 'Technology Assessment in Business and Government' Office of Technology Assessment, NTIS order #PB-273164', January 1977, at http://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk3/1977/7711_n.html

Pouloudi A. & Whitley E.A. (1997) 'Stakeholder Identification in Inter-Organizational Systems: Gaining Insights for Drug Use Management Systems' Euro. J. of Information Systems 6, 1 (1997) 1-14

Shackelford S.J. & Russell S. (2016) 'Operationalizing Cybersecurity Due Diligence: A Transatlantic Case Study' South Carolina Law Review 67, 3 (Spring 2016) 7, at https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4182&context=sclr

Schmidt M.J. (2005) 'Business Case Essentials: A Guide to Structure and Content' Solution Matrix , 2005, at http://www.solutionmatrix.de/downloads/Business_Case_Essentials.pdf

SoW (2013) 'Discounted Cash Flow Analysis' Street of Walls, 2013, at https://www.streetofwalls.com/finance-training-courses/investment-banking-technical-training/discounted-cash-flow-analysis/

Stobierski T. (2019) 'HOW TO DO A COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS & WHY IT'S IMPORTANT' Harvard Business School Online, September 2019, at https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/cost-benefit-analysis

Wahlstrom K. & Quirchmayr G. (2008) 'A Privacy-Enhancing Architecture for Databases' Journal of Research and Practice in Information Technology 40, 3 (August 2008) 151-162, at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.454.3815&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Wright D. & De Hert P. (eds) (2012) 'Privacy Impact Assessments' Springer, 2012

Wright D., Friedewald M. & Gellert R. (2015) 'Developing and testing a surveillance impact assessment methodology' International Data Privacy Law 5, 1 (2015) 40-53, at https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/data-crone-wright-2015a.pdf

Wright D. & Raab C.D. (2012) 'Constructing a surveillance impact assessment' Computer Law & Security Review 28, 6 (December 2012) 613-626, at https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/data-crone-wright-2012a.pdf

Wyman K.M. (2017) 'Taxi Regulation in the Age of Uber' N.Y.U. J. Legislation & Public Policy 20, 1 (April 2017) 1-100, at https://www.nyujlpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Wyman-Taxi-Regulation-in-the-Age-of-Uber-20nyujlpp1.pdf

Young R.C. & Jordan E. (2002) 'IT Governance and Risk Management: an integrated multi-stakeholder framework' Asia Pacific Decision Sciences Institute, Bangkok, 2002, at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.454.3272&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Adapted version of Clarke (2015, p.547-549)

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor associated with the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation in UNSW Law, and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 13 May 2022 - Last Amended: 13 May 2022 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/DV/MSRA-VIE.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy